The challenge … and the opportunity

A briefing for the incoming Minister for Tertiary Education and Skills

This briefing was prepared for the incoming Minister for Tertiary Education and Skills in the coalition government formed following the 2023 general election. The briefing was developed in association with Community Colleges New Zealand Ltd, a charitable company that manages services for young people at risk.

1 Summary and recommendations

Summary

One of the key problems facing the incoming government is how to improve outcomes for young people at risk of long-term limited employment. More than a fifth of each birth cohort is likely to reach the age of 24 facing medium or high risk of long-term limited employment.

Analysis by the Ministry of Education and by independent researchers has found that the government’s main programme for young people at risk – Youth Guarantee (YG) – is failing to deliver good employment outcomes. Those who complete a YG programme are more likely to be unemployed and more likely to be on a benefit than similar people who didn’t do YG.

This is because the government’s policy (and hence, programme design) is at odds with the way these young people – who face multiple challenges – make transitions.

We argue that it is possible to design programmes that work well for young people at risk. That will require government:

- to articulate clearly to that purpose of these programmes is to help young people make successful transitions and to minimise the risks they face of long-term limited employment

- to design programmes that have a primary focus on that purpose

- to require agencies to design processes that enhance that purpose

- to make changes to the way that the performance of these programmes is measured – to focus on assessing the value added by the programme and the outcomes for the individuals who take the programme.

Community Colleges NZ currently runs a programme called GROW (funded by MSD under He Poutama Rangatahi – Youth Employment Pathways) that illustrates how these ideas can work in practice.

2 Youth at risk

One of the most urgent problems facing New Zealand is the need to improve the transitions of young people from school to adulthood with sustainable, satisfying and rewarding employment. Too many young people face the risk of lives with limited employment and poor social outcomes. This is also a highly complex issue that cannot be addressed by ad hoc and disconnected interventions – we need a comprehensive and long-term approach.

Many school leavers are at risk of poor transitions …

Many young people leave school facing the risk of long-term limited employment – spells of unemployment and benefit dependency, periods unemployed, periods of under-employment, periods of low-skill work paid at the minimum wage, precarious employment and periods of enrolment in low-level tertiary education[1].

Nearly a quarter of each birth cohort is likely to reach the age of 24 facing medium or high risk of long-term limited employment[2].

Those who are in limited employment in early adulthood are likely to still be in limited employment for the following decade[3]

The cost of poor transitions is high …

Long-term limited employment has life-long negative impacts, ‘scarring’ a young person’s future job and earnings prospects[4]. Those who experience long-term limited employment face increased risk of becoming marginalised, involved in high-risk behaviour (for example, drug abuse or crime), housing problems or homelessness, poorer health and a lower quality of life[5]. This scarring affects not just the individual – there are also negative effects on families and communities. The impacts are inter-generational[6]. On the other hand, research shows that employability leads to better well-being, health and life satisfaction[7].

Poor transitions also impose costs on government, the economy and society at large; productivity suffers through the waste of human capital while government faces the costs of welfare benefits, social housing, justice interventions and, possibly, incarceration.

At the same time, New Zealand faces shortages of skilled workers as work becomes more sophisticated and requires more and different skills – core cognitive skills and, equally, socio-emotional skills[8].

And indicators suggest the problem is likely to get worse in the near future …

Overwhelmingly, young people at risk of long-term limited employment have no or low school achievement. New Zealand is one of seven countries that participate in the OECD’s PISA programme where the trend in performance in literacy, mathematics and science is declining[9].

That is a lead indicator that the number of people completing school with low achievement and low cognitive skills – and hence, at risk of long-term limited employment – is rising, rather than falling. This lead indicator suggests the problem is likely to get worse in the near future.

We need to work on the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff … as well as the fence at the top …

The seeds of these risks of long-term limited employment are sown early in life, in a child’s upbringing and family circumstances.

The best and most cost-effective time to intervene and address this risk is early in in a person’s life; the longer intervention is delayed, the more costly it will be and the less likely it is to succeed[10]. But this is a stock and flow problem; while it’s best to intervene early, we are already facing a large and growing number of people reaching young adulthood with the prospect of poor outcomes. We have to improve the way our systems manage the problem we are already facing[11].

3 New Zealand’s current approaches to managing youth at risk

The landscape …

The government has two main programmes designed to help young people at risk of poor transitions:

- Youth Guarantee funded through Vote Tertiary Education and managed by the TEC, created in 2010[12]

- The Youth Guarantee (YG) programme is targeted at young people with low educational achievement. The programme aims to help students gain qualifications at levels 1 or 2 on the NZ Qualifications and Credentials Framework (NZQCF) and to progress to higher level study. YG is delivered by Te Pūkenga (through its polytechnic subsidiaries), by wānanga and by private training establishments.

- YG replaced an earlier suite of programmes – including the now-discontinued Youth Training.

- Youth Service | Ratonga Taiohi, funded through Vote Social Development and managed by MSD, created in 2012

- Youth Service (YS) is delivered by community organisations, iwi organisations and private training establishments. The YS providers employ youth ‘coaches’ who run workshops, do one-on-one mentoring, help young people develop realistic career plans, help them prepare for job interviews and provide advice on practical matters like housing. YS has no training/education function; instead, coaches act as training and education brokers, mostly arranging for the young people they support to undertake YG study. Some young people who participate in a Youth Service receive living cost payments[13].

- YS replaced an earlier programme called the Independent Youth Benefit (IYB).

A decade after these two initiatives were created, it’s time to take stock and check out the effectiveness of these programmes in helping at risk youth make successful transitions – and in particular, to move into sustainable employment.

How well has Youth Guarantee performed

A quantitative study showed mixed results, with little effect on employment outcomes

The Ministry of Education’s monitoring of YG drew on administrative data (including Statistics NZ’s integrated data infrastructure (IDI)) to compare the outcomes for YG participants with young people who had matching characteristics but who didn’t take YG[14]. It sought to check out whether YG led to:

- improved achievement of educational qualifications at Level 2 or above

- better progression to higher levels of education

- sustained employment

- reduced incidence of being NEET

- reduced likelihood of being on a benefit

in the years following completion of the programme.

The most recent Ministry monitoring report, released in 2018, looked at the performance of the first five cohorts entering YG. It showed that educational performance by YG participants was generally better than for the comparison group:

- participants were more likely to have gained a qualification at level 2

- but there was no difference in the rate of progression to qualifications at level 4 or above.

But, crucially, the employment outcomes of participants were no better than for the comparison group:

- participants were no more likely to be in full-time employment

- participants were more likely to be NEET – not in employment education or training

- participants were more likely to be on a benefit.

A complementary qualitative study showed similar results

The findings of the Ministry’s monitoring resonate with a qualitative study[15] of YG participants, which collected information on a sample of young people who entered YG in 2015, using surveys and interviews, complemented by focus group sessions with YG provider staff. A subgroup of the students was interviewed in six phases over 2015 to 2019.

The analysis found that participants reported receiving significant academic support at their YG providers. After completing YG programmes, participants considered that their experience of the programme had a positive effect on their transitions, (likely reflecting the professionalism of YG providers). So the immediate impacts were positive.

But …. while most participants reported feeling well-prepared for the future upon exit from YG, this did not necessarily result in positive education and employment transition experiences. Many participants expected that the qualifications gained from YG would open up pathways which they had previously found difficult to access. But this wasn’t generally the case.

Overall?

YG earns, at best, a mixed report card. Good while it lasts, but on employment, the principal outcome YG was set up to achieve, the programme appears to have been ineffective. Where it really matters, YG has not worked.

Youth Service | Ratonga Taiohi

Findings on the performance of YS

The design of YS has many of the features of successful transition programmes – in particular, individual needs assessment, tailoring of plans to the participant’s needs, personal coaching, mentoring and case management and assistance with job seeking[16].

However, YS does not operate as a stand-alone transitions programme; YS coaches act as training brokers. Therefore, the effectiveness of YS depends on the performance of the education and training programmes that YS clients take – which is, for the most part, YG. That means that the effectiveness of YS is closely linked to the effectiveness of YG.

The Ministry of Social Development reported in June 2014 that those in the early cohorts in YS were more likely than those on the IYB (its predecessor programme) to have had success in education and there was ‘early evidence’ suggesting that YS ‘is improving participants’ prospects of moving off benefit’[17].

The Treasury evaluations

The Treasury published two evaluations of YS in 2016[18], using an analytical approach similar to the Ministry of Education’s YG monitoring report – ie, using data from the IDI to create a participant group and a comparison group.

The evaluations find that participation in YS increases the retention of participants in education and improves their educational attainment. But it was found to have led to no improvement in the likelihood of employment and appears to have raised, rather than lowered, participants’ likelihood of being on a benefit[19]).

Given that the effectiveness of YS depends on the effectiveness of YG, that finding is unsurprising; it mirrors the Ministry of Education’s findings on YG.

Overall?

The design of YS has many of the elements identified by McGirr and Earle (2019) as features of effective transitions programmes. But, for YS to be effective, it needs to be coupled with effective training programmes.

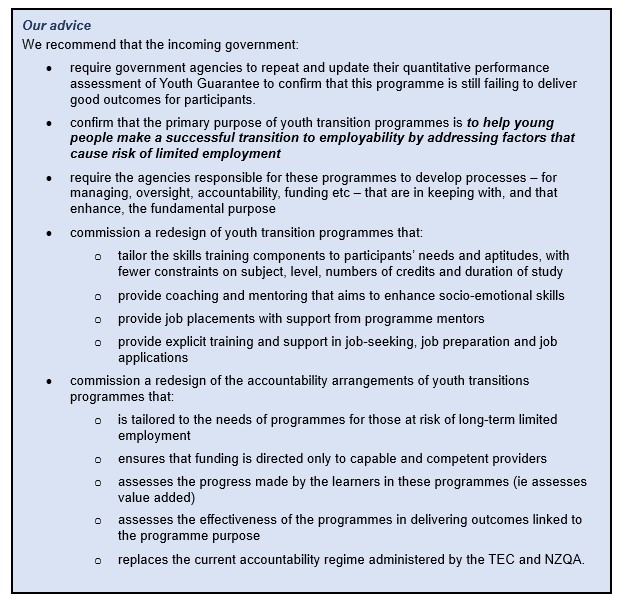

Our advice

We recommend that the incoming government:

- require government agencies to repeat and update their quantitative performance assessment of Youth Guarantee to confirm that this programme is still failing to deliver good outcomes for participants.

4 What’s gone wrong?

We need to see these results in context …

We need to see the depressing outcomes of YG and YS in their context. These programmes were set up to help people who had reached their mid teenage years with multiple problems.

McGirr and Earle’s (2019) analysis identifies those most at risk as those who left school with low or no qualifications, who have experienced inter-generational benefit dependency, who have had contact with the justice system or with Oranga Tamariki or who have become a young parent.

The qualitative research on YG by Reid and Schroder (2019) states that[20]:

Most participants did not complete secondary school and held few formal school qualifications when they entered Youth Guarantee. From the surveys and interviews, we learnt that the main reasons for this were related to poor relationships at school, bullying, mental health, poor behaviour and issues with learning and achievement …. A small group had experienced long periods of [being] not in employment, education or training (NEET) [before taking on YG]. Overall these participants reported earlier disengagement from education than the rest of the cohort.

That suggests that learning problems have been magnified by problems of adjustment and challenging social interactions.

Given that school achievement is linked to experiences in early childhood and family background[21], it is also highly likely that many of the people in YS and YG had also experienced a difficult upbringing.

These are interventions designed to deal with the stock problem, not the flow. They are directed at those who scaled the fence at the top of the cliff and fell. Economist James Heckman argues that the later an intervention is given to a disadvantaged child, the less effective it is likely to be. And later interventions are more likely to be more costly[22]. What is more, if untreated, gaps in skills between children can become more pronounced over time[23].

In other words, YG and YS are targeted to people with deep and complex challenges that are likely to have originated many years before – and have had time to fester and grow. These programmes have one of the most challenging tasks in the education system.

But we will likely need ambulances at the foot of the cliff for decades, if not forever …

New Zealand must address both the flow and the stock; even if we were entirely successful in solving the flow problem and addressing the challenges of this group from birth and in early childhood, it would take more than a decade and a half before today’s new-borns and pre-schoolers reach the end of high school when we get to see the benefit of the first green shoots of the solution. And decades before we could expect to see the full benefits of that work.

Therefore, the stock problem will remain; government needs to look at if, and how, it can improve its services to youth at risk, deliver better preparation for employment to young people and get better value for its expenditure.

What do we know about what is causing these programmes to fail

In their review of the performance of YG, having tracked and interviewed participants and having conducted focus groups with YG staff, Reid and Schroder (2019) conclude:

Policy in … foundation education does not currently align with the realities of young people’s education and employment transitions … policy dictates the structure, delivery and outcomes of Youth Guarantee Fees Free in a manner which assumes a linear transition through education to employment. The findings of this project clearly indicate that young people’s transitions are iterative, complex … [and] the needs and challenges of this group of young people cannot be met through education alone. …

Future policy … should consider the value of holistic and ongoing support … Programmes which have greater flexibility to meet individual student needs, support collaboration between agencies working with young people and which focus on longer-term positive outcomes rather than immediate outputs, such as qualifications, are more likely to have a sustained positive effect[24] …

Funding of tertiary education – YG included – depends on performance and performance is measured by the TEC through a set of educational performance indicators (EPIs) that include qualification completion rates and course completion rates[25]. Reid and Schroder (2019) are suggesting that this regime creates incentives on YG providers to ‘chase’ completions at the expense of outcomes (such as employability and the acquisition of socio-emotional skills that are strong predictors of employment outcomes[26]).

In addition, until 2023, students in YG were required to be enrolled in courses amounting to 100 credits to count as full-time for funding purposes (whereas each level of NCEA requires only 80 credits[27]). For 2023, the government reduced the expected credit load for full-time funding from 100 credits to 80 credits, equal to each level of NCEA – for a group of students whose educational history suggests that that load would be very challenging if not downright unrealistic.

Valuing what is measurable

The discussion above is an example of a problem that dogs educational performance assessment world-wide – valuing what is measurable at the expense of measuring what is valuable[28].

Performance monitoring is a critical part of the accountability requirements for any public funding. And accountability requires an assessment, a measurement, of performance. But, if performance measurement that underpins monitoring is not well-aligned to the outcomes we seek from a programme, it will create perverse incentives. Providers respond to incentive; if funding is linked to credits and qualification completions, providers will strive to deliver credits and qualification completions. But YG was created to serve a wider goal – improving the transition to adulthood (including the qualities needed for sustainable employment) for young people whose poor educational performance or whose socio-emotional skill level means that they are at serious risk of long-term limited employment.

This is the misalignment identified by Reid and Schroder (2019).

Measuring what is valuable

Transitions programmes are intended to help young people minimise the risk of long-term limited employment. They should be designed to enable successful transitions to sustainable employment. That means gaining skills – socio-emotional skills as well as some cognitive skills. It means also recognising the value added to individuals by the participation in the programme.

If that’s what transitions programmes aspire to, that is how the monitoring and, consequently, the measurement, should be shaped.

Most of what is valuable is harder to measure than counting credits and qualifications. Parts would require qualitative measurement.

How we might do that is covered in Section 5 of this paper.

5 Principles underpinning the design of programmes for youth at risk

The evidence presented above suggests that the incoming government needs to reset its approach to programmes for youth at risk. Despite much positive work from providers, neither YG nor YS appears to have delivered on the fundamental goal of programmes of this kind – which is to help young people with low or no qualifications and who face high risk of long-term limited employment gain the qualities, attributes and skills needed for the transition to sustainable employment.

We propose that the incoming government take the opportunity to take a fresh look at these kinds of programmes and commission agencies to develop a full redesign of these programmes. We have set out here the principles that should inform that redesign.

Clarifying the purpose

The first step in redesign is to clarify and articulate the primary goal of these programmes.

It needs to be central to the design of these programmes that they are for the purpose of helping young people make a successful transition to employability by addressing factors that cause risk of limited employment.

That means committing to a fundamental reshaping of YG to create a new programme (or new programmes) designed around that purpose.

Secondly, the agencies responsible for these programmes need to commit to developing processes – for managing, oversight, accountability, funding etc – that are in keeping with, and that enhance, the fundamental purpose.

In other words, agency processes need to ensure that providers have the capability and resources to deliver on the purpose, that the delivery of the programmes – teaching /guidance/mentoring etc – is structured around that purpose, and, most importantly, that the approaches taken to the design of accountability and funding mechanisms (which set the incentives that drive provider behaviour and performance) are structured in ways that support the programme goal. There is a need to avoid the kind of mismatch between accountability and purpose that has characterised YG.

Looking at what works

In their review of evidence of what works in programmes for youth at risk, McGirr and Earle (2019) suggest that successful programmes:

- include work experience or a component of on-job training

- offer assistance in job seeking

- value success broadly – ie beyond academic/qualifications

- offer holistic support (such as one-on-one mentoring) to participants

- are closely targeted to the needs of their participants

- are aligned with particular labour market needs.

They suggest that, in the absence of those characteristics, skills training programmes (such as the type of training offered in most YG programmes) are the least effective of all.

That summary complements the findings of Reid and Schroder (2019). They identify a misalignment between the structure of YG programmes and the iterative, non-linear pattern of most young people’s transitions. Therefore, they argue for a reduced emphasis on qualifications, greater flexibility to cater for individuals’ needs and more holistic support.

Therefore, in reconsidering the shape of programmes for young people at risk, the incoming government should look to programmes to replace YG that:

- place less emphasis on academic and skills training, allowing providers to tailor the skills training component to a participant’s needs and aptitudes, with fewer constraints on subject, level, numbers of credits and duration of study, possibly allowing participants to move into and out of that part of the programme, around the other programme elements

- provide coaching and mentoring that aims to enhance socio-emotional skills

- provide job placements with support from programme mentors

- provide explicit training and support in job-seeking, job preparation and job applications.

Accountability

Accountability for performance is a prerequisite for continuing to receive public funding. But aligning an accountability regime to the purpose described above poses particular challenges.

One of the reasons for the design of the current accountability approach is that it is efficient and timely – counting of credits attempted and credits achieved, for instance, is straightforward administratively and is readily fitted to an annual cycle. But if a programme’s purpose is employment-related, then the accountability regime needs to place a greater emphasis on outcomes – which are not so easily captured in administrative systems and which are realised over a longer time-frame, outside of the period a participant is engaged in the programme.

And employment outcomes, as envisaged in that purpose, go beyond the binary question “is the person in paid employment?”. The outcomes we seek need also to consider employability. That needs a qualitative assessment, not merely quantitative. The purpose of the programme entails helping participants to enhance their socio-emotional skills; that, too, will need qualitative assessment.

Finally, it was noted in section 5 of this paper that participants in these programmes are, by definition, among the most disadvantaged in the education system. Therefore, the accountability regime needs to be tempered by that context. That entails a need to assess the progress a participant has made while on the programme, an assessment of value-added. That, too, requires qualitative assessment.

That kind of accountability will be more complex for the TEC and NZQA. However, it is no more so than the array of checks that the agencies currently subject providers of YG to – through the TEC funding conditions and through NZQA’s external evaluation and review process (which involves periodic qualitative assessment by an expert panel). Those accountability regimes have been designed around the expectations and the needs of providers of qualifications at Level 4+, but have been applied also, inappropriately and without tailoring, to adult foundation education.

It would be possible to design an accountability regime that is no more costly or compliance heavy to replace the current TEC and NZQA requirements that:

- is tailored to the needs of programmes for those at risk of long-term limited employment

- ensures that funding is directed only to capable and competent providers

- assesses the progress made by the learners in these programmes

- assesses the effectiveness of the programmes is delivering good outcomes for their students

- in effect, replaces the current accountability regime administered by the TEC and NZQA.

Our advice

We recommend that the incoming government:

- confirm that the primary purpose of youth transition programmes is: to help young people make a successful transition to employability by addressing factors that cause risk of limited employment

- require the agencies responsible for these programmes to develop processes – for managing, oversight, accountability, funding etc – that are in keeping with, and that enhance, the fundamental purpose

- commission a redesign of youth transition programmes that:

- tailor skills training component to participants’ needs and aptitudes, with fewer constraints on subject, level, numbers of credits and duration of study

- provide coaching and mentoring that aims to enhance socio-emotional skills

- provide job placements with support from programme mentors

- provide explicit training and support in job-seeking, job preparation and job applications

- commission a redesign of the accountability arrangements of youth transitions programmes that:

- is tailored to the needs of programmes for those at risk of long-term limited employment

- ensures that funding is directed only to capable and competent providers

- assesses the progress made by the learners in these programmes (ie assesses value added)

- assesses the effectiveness of the programmes in delivering outcomes linked to the programme purpose

- replaces the current accountability regime administered by the TEC and NZQA.

6 Case study: The Community Colleges GROW programme

Section 5 above discusses the principles that should underpin the design of sound programmes that help those at risk of long-term limited unemployment to transition to employability. But is it actually possible to design and implement a programme that meets those conditions?

Community Colleges Ltd, a South Island charitable company that manages services for young people at risk, has established and is conducting the GROW programme – Goals, Resilience, Opportunity, Wellbeing. That programme embodies those principles of design.

The GROW programme has an initial 12-week group delivery component, followed by individualised one-on-one mentoring for rangatahi aged 15-24 who are NEET. Each GROW intake involves 10 rangatahi with a dedicated tutor. Most participants left school at 15 or younger. Most face multiple challenges – such as family issues, learning difficulties, mental health, self-esteem – which create barriers to educational achievement and to employment.

Community Colleges is well-connected to its North Canterbury community and employers, creating opportunities for bridging to employment or to further skills training.

GROW is funded by MSD’s Work and Income through its He Poutama Rangatahi programme.

GROW has the characteristics of successful transitions programmes identified in McGirr and Earle’s (2019) review of what works in foundation education.

Community Colleges argues that it delivers successful outcomes because the organisation has a “focus on meeting needs rather than merely following rules”.

While GROW’s approach is a learner pathway focusing on sustainability and food security, this model provides a template that can be used to create programmes in other vocational areas.

7 A profile of Community Colleges NZ Ltd

Community Colleges NZ Ltd (ComCol) is a registered charitable company that provides MSD’s Youth Service | Ratonga Taiohi in the South Island and that provides training programmes for young people at risk.

ComCol’s whakataukī reflects its vision, focus and values:

Poipoia te kākano kia puawai – Nurture the seed and it will blossom

ComCol grew from the Rangiora Enterprise Trust, founded in 1983 to offer vocational training to young people. That organisation evolved into the Academy Group, a national provider of training for young people. When the Academy Group split in 2001, ComCol was established to manage most of the South Island work of the Group.

Over the last 40 years, the training programmes offered by ComCol and its predecessors have been funded through a range of government schemes – including Access, Training Opportunities, Youth Guarantee and He Poutama Rangatahi.

On the basis of external evaluation and review, NZQA rated ComCol a Category 1 provider, the highest category, in its two most recent reviews – 2016 and 2020.

ComCol’s founder and governing director, Tony Hall, CNZM, is recognised as a pioneer in foundation education for young people at risk. He was appointed by the government to the board of NZQA between 1992 and 1999, as a member of the Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (2002-2003) and a board member of the TEC (2009-2012). Tony was also a Ministerial appointee to the University of Canterbury council (2013-2017) and a member of the Lincoln University council (2004 – 2017), becoming Chancellor in 2016-2017. Among his other governance roles, Tony has been as a director of CORE Education Ltd, as a member of the boards of the NZ Olympic Committee, High Performance Sport NZ, Enterprise North Canterbury and MainPower.

Bibliography

References

Berntson E (2008) Employability perceptions: nature, determinants and implications for health and well-being Psykologiska institutionen, Stockholm University

Biesta G (2009) Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education Educational Assessment Evaluation and Accountability

Carneiro P, Cunha F and Heckman J (2003) Interpreting the evidence of family influence on child development Research Gate

Cunha F and Heckman J (2007) The technology of skill formation NBER Working Paper No 12840 National Bureau of Economic Research

Community Colleges (2021) A better delivery for our youth students: discussion paper, Community Colleges NZ (available from Community Colleges NZ Ltd)

Community Colleges (nd) Regional Youth Development Strategy Community Colleges NZ and Matairangi Mātauranga (available from Community Colleges NZ Ltd)

Dixon S and Crichton S (2016) Evaluation of the impact of Youth Service: NEET programme, Treasury Working Paper 16/08, The Treasury

Drake R and Wallach M (2020) Employment is a critical mental health intervention Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 2020 29:e178

Earle D (2018) Monitoring Youth Guarantee 2017: Youth Guarantee Fees-Free places, Ministry of Education

Hanushek E (2011) The economic value of higher teacher quality Economics of Education Review, vol. 30, pp. 466–479

Heckman J (2011) The economics of inequality: the value of early childhood education American Educator, Spring 2011

Higgins J (2002) Young people and transitions policies in New Zealand Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. (18). 44-61.

MBIE, MoE, MSD and MfW (2023) Preparing all young people for satisfying and rewarding working lives: Long-Term Insights Briefing Ministries of Business, Innovation and Employment, of Education and of Social Development, Ministry for Women

McGirr M and Earle D (2019) Not just about NEETs: a rapid review of the evidence on what works for youth at risk of limited employment Ministry of Education

McLeod K, Dixon S and Crichton S (2016) Evaluation of the impact of Youth Service: Youth Payment and Young Parent Payment, Treasury Working Paper 16/07, The Treasury

Mhuru M (2023) Exploring young people’s experience of limited employment Ministry of Education

MSD (2014) Youth Service Evaluation Ministry of Social Development

Nedelkoska L and Quintini G (2018) Automation, skills use and training OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing

NZQA (2020) Community Colleges NZ Ltd external evaluation and review report NZQA

NZQA (2016) Community Colleges NZ Ltd external evaluation and review report NZQA

NZQA (2023) Case study Community Colleges NZQA (to be published shortly)

OECD (2019) PISA 2018 results: what students know and can do: Volume 1 OECD Publishing.

Pacheco G and Dye J (2013) Estimating the cost of youth disengagement in New Zealand NZ Journal of Employment Relations 38(2)

Productivity Commission (2020) Technological change and the future of work NZ Productivity Commission

Reid A and Schroder R (2019) Youth Guarantee pathways and profiles project: final report The Collaborative Trust and Ako Aotearoa

Sense Partners (2021) Addressing labour market scarring in a recession: issues and options Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu

Samoilenko A and Carter K (2015) Economic outcomes of youth not in education, employment or training (NEET) Treasury Working Paper 15/01 The Treasury

Silla I, De Cuyper N, Gracia F, Peiró J and De Witte H (2008) Job insecurity and well-being: moderation by employability Journal of Happiness Studies 10, 730-751

Smyth R (2023a) Making successful transitions Strategy, Policy, Analysis, Tertiary Education

Smyth R (2023b) No easy fixes Strategy, Policy, Analysis, Tertiary Education

Vanhercke D, De Cuyper N and De Witte H (2016) Perceived employability and wellbeing Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 14 (2016), 8-18

Websites consulted

Community Colleges NZ Ltd About us

Community Colleges NZ Ltd GROW course

Ministry of Education Youth Guarantee

Ministry of Social Development youth service | ratonga taiohi

New Zealand Qualifications Authority NCEA

New Zealand Qualifications Authority External evaluation and review

New Zealand Qualifications Authority Community Colleges NZ Ltd, External evaluation and review

New Zealand Qualifications Authority Provider categories after EER

Tertiary Education Commission Youth Guarantee

Tertiary Education Commission Performance of tertiary education organisations

Work and Income He Poutama Rangatahi – Youth Employment Pathways

Endnotes

[1] McGirr and Earle (2019), MBIE et al (2023), Mhuru (2023). The term ‘long-term limited employment’ has superseded that former, somewhat misleading description ‘NEET’. See McGirr and Earle (2023) pp1, 5-6 and Mhuru pp1-3

[2] McGirr and Earle (2019) report that the figure in the year 2015 was around 22% – see page 26.

[3] Mhuru (2023) – see pp30 et ff

[4] MBIE et al (2023), Sense Partners (2021), Samoilenko and Carter (2015)

[5] Pacheo and Dye (2013), Samoilenko and Carter (2015), Smyth (2023a)

[6] McGirr and Earle (2019), Sense Partners (2021), MBIE et al (2023)

[7] Silla et al (2008), Vanhercke et al (2016), Berntsen (2008)

[8] NZ Productivity Commission (2020), Nedeloska and Quintini (2018). Note that the OECD now uses the term ‘socio-emotional skills’ rather than the former term ‘non-cognitive skills’ (which describes what these skills are not, rather than what they are) and the imprecise term ‘soft skills’.

[9] OECD (2019)

[10] Heckman (2011), Smyth (2023b)

[11] Smyth (2023b)

[12] The YG programme comprises two strands – YG fees free courses and Trades Academies (TAs). TAs are funded through Vote Education; they are centred in high schools but offer trades training aligned to one of six vocational pathways – usually in partnership with a tertiary education organisation. In practice, TAs serve a different function from the YG fees-free programme managed by the TEC. TAs create pathways for students who have an ambition to transition to vocational education; they are relatively selective. Therefore, students at risk of poor transitions are unlikely to follow that path. Therefore, this paper looks only at the YG fees free programme and not at TAs.

[13] Living cost payments are available to those who are aged 16-19 and caring for a child or aged 16 or 17 and unable to live at home or be financially supported by their families.

[14] Earle (2018)

[15] Reid and Schroder (2019)

[16] McGirr and Earle (2019) pp2, 3 summarises the literature on what works in transition programme design.

[17] MSD (2014). The report covers only participants in the first 18 months of the operation of YS. The comparison group used was of people on the IYB and similar emergency benefits for 16–18-year-olds.

[18] McLeod, Dixon and Crichton (2016) and Dixon and Crichton (2016)

[19] However, evaluators found evidence that recipients of the YS Young Parent Payment are ‘somewhat more likely’ to move off a benefit after 24-30 months.

[20] Reid and Schroder (2019) page ii

[21] Carneiro, Cunha and Heckman (2003), Cunha and Heckman (2007) and Heckman (2011)

[22] Cunha and Heckman (2007)

[23] Hanushek (2011)

[24] Reid and Schroder (2019) page vii. See also Higgins (2002) who makes a similar point about transitions pathways.

[25] See the TEC performance measurement page.

[26] McGirr and Earle (2019) pp 32-33.

[27] See this page on the NZQA website.

[28] See Biesta (2009)