New data helps us find out

It’s well known that there is a strong relationship between educational attainment and better outcomes – employment outcomes and also outcomes like life satisfaction, political efficacy and the like[1]. Education is linked to benefits, both for individual participants and for societies. But even if education is a factor in driving outcomes, it’s only one of many factors. Even the most sophisticated and comprehensive statistical models of outcomes give only part of the picture[2].

The problem is that educational attainment is the product of multiple factors, many of them unmeasured, many unmeasurable. And the drivers of longer-term outcomes of education are even more complex. Qualifications and attainment tell only part of the story. Think about so-called “soft skills” – factors like ambition, conscientiousness, emotional stability. And about cognitive skills (such as literacy, numeracy and problem solving – factors that are related to, but separable from, educational attainment). Plus personal characteristics – socio-economic status, cultural and demographic factors – will play a part in shaping outcomes. Attitudes such as agreeableness, optimism. Think of the effects of health, of the influence of peers, of family stability and the quality of parenting[3].

Given that complexity, given the multiple drivers of outcomes, given that some powerful influences of outcomes are unmeasured and therefore, invisible in our main datasets (even in the IDI), we have little idea of how all those factors work together, which are more important in shaping outcomes – for instance, what is the relative importance of cognitive skills, educational attainment and soft skills in driving outcomes.

That gap is the real challenge for those interested in how educational policy can affect life outcomes for individuals and the society.

So it was a significant step forward, a really great step forward, late last month when the OECD published a report – Skills that Matter for Success and Well-being in Adulthood – from the 2023 Survey of Adult Skills, a report that put data on people’s employment, earnings and well-being alongside family background data, educational attainment data and data on their cognitive and information processing skills PLUS (and this is new, this is the gem) data on their social and emotional skills, what used to be called non-cognitive skills. A breakthrough report.

Reporting on social and emotional skills

The Survey of Adult Skills, part of the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), was first held in 2013/14, testing literacy, numeracy and problem solving and analysing the results in the context of respondents’ education, employment, earnings, health, life and job satisfaction and social behaviour. The second cycle of the survey was conducted in 2023. It included, as a new feature, a set of questions designed to make an assessment of socio-emotional skills. The earlier survey broke new ground in understanding education and skills in our society. But the 2023 data takes us further, much further, providing a deeper, richer view of the factors driving good outcomes.

The Big Five social and emotional skills

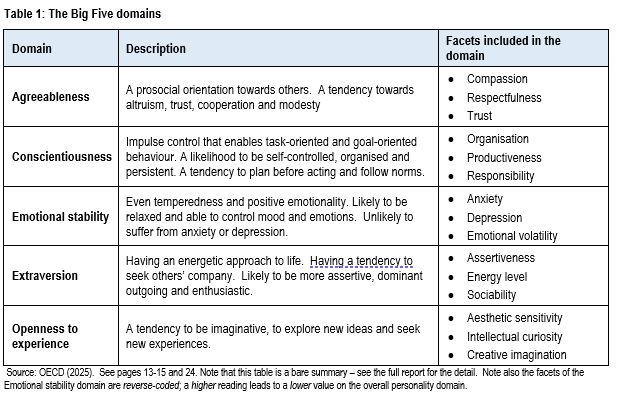

The survey incorporated questions that led to an assessment of respondents’ skills on what is known as the Big Five domains. The Big Five domains have been established, analysed, tested and refined over more than thirty years in the psychology research literature. They are summarised in Table 1 below:

These domains are not binary; each represents a range of behaviours. On the basis of responses to the Big Five Inventory questionnaire, each respondent is assigned a numeric score on each domain.

Thirty-one OECD countries took the Survey of Adult Skills and 29 of them (all but the US and Japan) used the Big Five module of the survey. Each country’s data on each of the Big Five domains has been scaled to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, so we can’t compare the social and emotional skills of New Zealanders with, for instance, the Finnish or Irish population.

But what the data does allow is to compare how differences in (say) conscientiousness affect outcomes in each country and to compare the impact of differences in conscientiousness between the countries. It allows us to see how much these socio-emotional skills influence outcomes, to assess the strength of their influence against the influence of qualifications and skills, and to compare those assessments with comparable countries.

That’s the breakthrough.

What the new OECD report does

The OECD presents a mass of data on social and emotional skills in the 29 countries.

- It examines how social and emotional skills help people build their education and their cognitive skills – like literacy, numeracy and problem-solving. It also presents data that shows how cognitive skills and formal education can affect the development of social and emotional skills, particularly in childhood and adolescence.

- It explains how social and emotional skills are distributed in the population – for instance, by age, by gender, by educational attainment and by respondents’ parents’ educational attainment.

- It also looks at how social and emotional skills, cognitive skills and educational attainment together affect outcomes, both employment outcomes and also social outcomes.

It’s that third part that I look at in this article. I look at the data for New Zealand on employment, earnings, life satisfaction and self-reported health status and I compare how differences in New Zealand respondents’ social and emotional skills affect those outcomes, taking account of respondents’ educational attainment, literacy, gender, age, and other background variables – and I compare that with the OECD average and with a small set of comparator countries.

I don’t do any fancy analysis – most of what I set out here is drawn directly from the OECD data. This is a teaser that illustrates the power and importance of the data; For more sophisticated analysis, you’ll have to wait for the Ministry of Education reports on social and emotional skills.

How New Zealanders’ outcomes are affected by their social and emotional skills

It’s really useful to look at the relative importance of factors like educational attainment, cognitive skills (like literacy) and social and economic skills.

The OECD’s new analysis does this by looking at the effect on an outcome of a one standard deviation increase in a Big Five domain score, controlling for other factors, controlling for educational attainment, for skill level and for social background. They assess the impact of each of the Big Five domains, comparing that with the effect of other factors.

I look at New Zealand’s results compared with the OECD average and also with comparator countries – Denmark, Finland, Ireland and Norway, all high-income countries with a population of between five and six million[5].

Question 1: How do social and emotional skills affect the likelihood of being employed?

We know that employers want to recruit people who have social and emotional skills: Careers NZ reports that there are seven “essential employability skills” including having a positive attitude, self-management, a willingness to learn and resilience. Those don’t have a precise mapping to the Big Five domains but they overlap.

But employers also need their workers to have technical skills – trade skills (like building skills) or professional skills (like nursing). What this new OECD data gives is a view of how employers balance those two needs, how the technical and socio-emotional skills are weighed and how much impact each has on the employment decision. Employers are sometimes outspoken in their advocacy for soft skills. But how does that play out in their decisions on who to employ, who to promote? What are the revealed preferences of employers?

That’s a key issue for education policy and education design, particularly for tertiary education.

The graphs below suggest that New Zealanders with greater conscientiousness and higher levels of emotional stability are more likely to be employed; however, agreeableness and openness are negative factors.

But in New Zealand and across the OECD, the effect of literacy on the likelihood of being employed is greater than any of the socio-emotional skills. In other words, cognitive skills are not out-weighed by socio-emotional skills.

Literacy outweighs Big Five factors in predicting employment

The New Zealand results are broadly similar to those across the 29 participating OECD countries, except that the negative effect of Agreeableness and Openness is larger among the New Zealand survey respondents.

Figure 1b reproduces the data from Figure 1a but also adds the data from the four comparator countries.

The effect of a change in social and emotional skill level differs according to people’s literacy level; among those with high literacy, the effect is muted while among those with low literacy the effect of a change in socio-emotional skill can be pronounced. That implies that, when recruiting among people with lower cognitive skills, employers take greater account of the soft skills and conversely. In particular, conscientiousness has a very large impact on the likelihood of being employed among those with low literacy.

Figure 1c looks at the effect on likelihood of employment of a one standard deviation change in socio-emotional skill level – comparing those with low literacy and those with relatively higher literacy.

The Big Five factors carry more weight on employment when we focus on those with lower literacy

So overall?

The analysis suggests that some social and emotional skills – Conscientiousness and Emotional stability – are important factors in decisions on who to employ in the New Zealand labour market, but their importance is larger among those with lower cognitive skills. In other words, in jobs that require significant technical and cognitive skills, the importance of social and emotional skills is muted.

And employers in New Zealand are less persuaded by factors like Agreeableness and Openness, again, especially among those with lower literacy.

Question 2: For those in work, how do social and emotional skills affect earnings?

Once in employment, people’s value to their employer, their advancement through the ranks, is proxied by their earnings. Those who deliver greater value to the firm can be expected to be rewarded over time with promotion and higher wages. How do the Big Five factors affect earnings? How does that compare with the effect of technical skills?

The OECD modelled the survey data to get a picture of whether an increase of one standard deviation in each of the Big Five scores was associated with higher earnings and if so, by how much.

The graphs below show that over the OECD as a whole, there is a moderate positive relationship between socio-emotional skills and wages. New Zealanders in work who have higher levels of Emotional stability tend to earn a little more, while the effect of an increase in the other Big Five domains is slight and not significant at the 5% level. But the effect of literacy skills is very significant.

Workers’ earnings are affected more by their literacy skills than by the Big Five factors

Figure 2b reproduces the data from Figure 2a but also adds the data from the four comparator countries.

The pattern is broadly similar in the comparator countries, although, in those countries, nearly all of the data is significant at the 5% level.

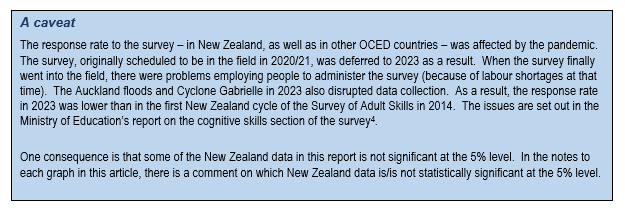

To weigh the importance of social and emotional skills as a factor in influencing the level of workers’ earnings, the OECD used their modelling to create a decomposition of the factors that influence wages, enabling us to see the relative importance of different factors – literacy skills, years of education, job tenure, field of study and “individual characteristics” (meaning gender, age, immigrant background, parental education, having children and living with a partner).

The Big five factors explain only a small proportion of variation in workers’ earnings …

Essentially, the overall message is that, even if social and emotional skills do influence workers’ earnings, they are much less important than factors like literacy, educational attainment and field of study.

But when it comes to job satisfaction, the tables are reversed; that’s hardly surprising! In nearly all countries, social and emotional skills – especially emotional stability and agreeableness – outweigh the effect of literacy on job satisfaction. However, New Zealand is an outlier in that Literacy is strongly and significantly associated with job satisfaction – possibly indicating that those with higher cognitive skills get assigned to more satisfying tasks[6].

… but, across the OECD, job satisfaction is affected by emotional stability and agreeableness more than by literacy

Question 3 How do social and emotional skills influence non-market outcomes?

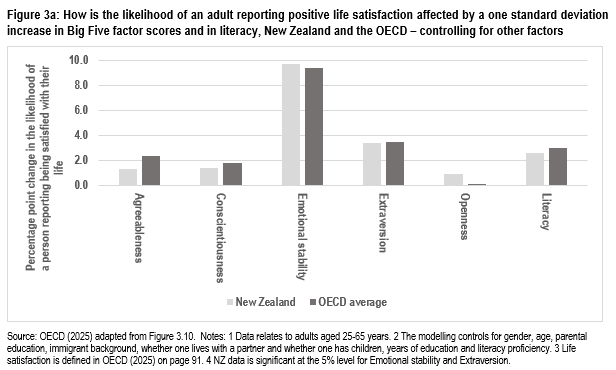

The discussion of job satisfaction raises the question about life satisfaction – how are readings of the Big Five factors related to life satisfaction and to matters like health status and other non-market outcomes?

Emotional stability and extraversion are statistically significant predictors of life satisfaction for New Zealanders, controlling for a range of background variables.

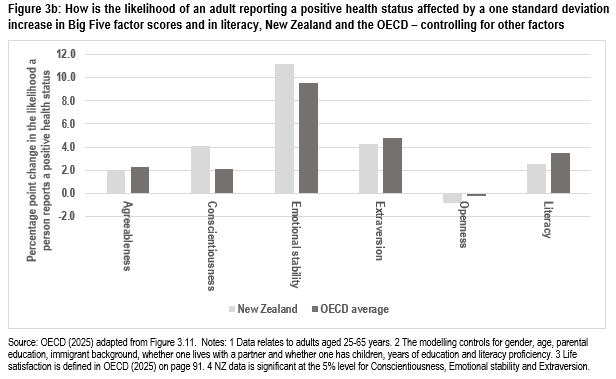

Figure 3b applies the same sort of analysis to self-reported health status, finding that Conscientiousness, Emotional stability and Extraversion are all related to positive health status.

A breakthrough but just a first step …

This new data on social and emotional skills is a breakthrough…

Being able to weigh social and emotional skills against cognitive skills and against education – that is very powerful. It enables us to assess how those skills affect outcomes. It enables us to understand behaviour in the labour market and to assess what matters for well-being. That gives food for thought in educational process design, in educational policy.

This note just touches the surface of what is possible from the data. I would expect that the Ministry of Education’s analysts will start to release deeper, more sophisticated, better targeted analyses over the next few months. For instance, extending the sorts of approaches used in Figures 1c and 2c above, which give a sense of the revealed (rather than the articulated) preferences of people. They will apply sophisticated statistical techniques … the opportunities are boundless. Perhaps they will lodge the data in the IDI, creating even greater analytical depth and breadth.

I am looking forward to seeing what comes out.

… but it’s not quite there yet

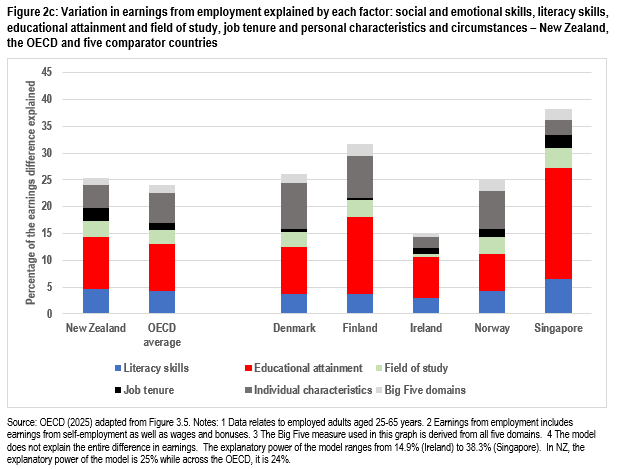

Nearly all countries had lower response rates to the 2023 cycle of the Survey of Adult Skills as a result of the pandemic. In part that was due to the way the pandemic affected people’s attitudes and behaviours[7]. In this country, those impacts were exacerbated by the challenge of recruiting survey administrators in a very tight labour market in 2022/23 and by two natural disasters in early 2023[8].

One consequence of the lower response rate is that some responses did not meet the threshold for statistical significance at the 5% level – that limits the scope for analysis. It also raises the risk of non-response bias.

We can only hope that there is a third cycle, that the third cycle extends the emphasis on social and emotional skills, that response rates lift and that those who analyse, interpret and report on the data apply creative and useful ways of developing usable information from it.

Bibliography

Brennan J, Durazzi N and Tanguy S (2013) Things we know and don’t know about the wider benefits of higher education: a review of the recent literature. BIS Research Paper, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

Cunha F and Heckman J (2007) The technology of skill formation NBER Working Paper No 12840 National Bureau of Economic Research

Earle D (2018) Factors associated with achievement in tertiary education up to age 20 Ministry of Education

Earle D, Satherley P and Marshall N (2024) Skills in New Zealand Ministry of Education

Heckman J (2011) The economics of inequality: the value of early childhood education American Educator, Spring 2011

OECD (2025) Skills that matter for success and well‑being in adulthood OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing

OECD (2024) Do adults have the skills they need to thrive in a changing world? OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing

Oreopoulos P and Petronijevic U (2013) Making college worth it: a review of research on the returns to higher education NBER Working Paper 19053 National Bureau of Economic Research

Pascarella E and Terenzini P (2005) How college affects students: a third decade of research Jossey-Bass

Scott D (2025) A review of the New Zealand evidence on the benefits of tertiary education Ministry of Education

Endnotes

[1] For an excellent overview of the NZ evidence, see David Scott’s excellent summary of dozens of studies. Likewise, there is much international research on the topic. See for instance Brennan et al (2013), Oreopoulos and Petronijevic (2013) and Pascarella and Terenzini (2005) for just some of many examples.

[2] For instance, Dee Earle’s 2018 groundbreaking analysis of factors influencing educational participation and achievement used a mass of variables from the IDI to examine how factors like socio-economic status, parental education and family background, as well as demographic and educational data to look at access and achievement. But the explanatory power of the models was only 35% or less.

[3] See, for instance, Heckman (2011) and Cunha and Heckman (2007).

[4] Earle, Satherley and Marshall (2024). See page 4 and page 7.

[5] Singapore was the other participating country with that population range. However, in some assessments, cases the Singapore results were not significant, the pattern of responses was at variance with the OECD and with the other four comparators. Because, in those cases, the readings were not statistically significant, it wasn’t clear whether the difference was “true”.

[6] Ireland is also an outlier; a one standard deviation increase in literacy increases the probability of a NZ worker reporting job satisfaction by 3.8 percentage points. For Ireland, the figure is an increase of 2.3 percentage points, while for the OECD as a whole, it is a fall of 0.1 percentage point.

[7] OECD (2024)

[8] See Earle, Satherley and Marshall (2024)