A submission in response to Number 7 of the University Advisory Group’s questions.

| Executive summary Matching university teaching to national needs New Zealand has a poor record in managing skill gaps. Many previous attempts to deal with shortages by trying to shift university enrolments have failed because of inadequate problem analysis. In those circumstances, there is a risk that the problem gets captured by the loudest voices. Every mismatch issue involves a unique set of causes involving some or all of emigration, immigration, the volume or quality of tertiary education graduates and a range of demand-side factors (such as remuneration levels, conditions of employment and reputational issues). One successful model was the E2E Engineering project, 2014/18, coordinated by the TEC involving the engineering profession and tertiary education institutions (not just universities). The first step in managing problems of mismatch is to establish a pro-active monitoring mechanism that will seek to identify matching issues – involving the perspectives of the tertiary education agencies, as well as the migration and labour market analysts. When a problem is identified, there needs to be sophisticated analysis to establish the cause and to set a tailored approach to fixing the issue. Another important matching question relates to how well university teaching (at senior levels) engages with the knowledge frontier in the field – a graduate quality issue. It is likely that this is variable in NZ (as in other countries). This finding places an important obligation on university heads of departments to manage the quality of teaching in their fields of responsibility. But one of the important lessons of recent history is that enrolments funding needs to remain underpinned by student choice … the research shows that students choose on the basis of their interests and aptitudes as well as their perception of their desired career and that attempts to manage it by other mechanisms usually have unfortunate consequences. Matching university research to national needs University statutory autonomy means that there are no command levers for government, business or community groups to pull in order to shape university research in ways that meet national needs. So … If the country wants to refocus university research in a more strategic direction, it is necessary to fund it, either through existing competitive government funding streams or by contracting the university to do the research[1] …. and …Each university needs to ensure that each specialisation/ discipline/ field of research Is led by people expert in the field, familiar with the knowledge frontier in the area and with the skills and connections that enable them to act as brokers – communicating the community’s needs to researchers and researchers’ capability to potential research consumers. |

Context

Any major strategic review of tertiary education inevitably deals with the question of matching the specialisations of the university system to national needs. National progress – economic and social –depends in large measure on human capital[1], on the ability of the people and our institutions to innovate. And to make use of the skills of the population and the technical knowledge held by skilled individuals. Tertiary education is the major supplier of skills to the labour market, a large producer of human capital, a store, disseminator and creator of knowledge. It is this factor that justifies the large public subsidy for tertiary education.

But it’s a question that has a chequered history…

In 2000, the Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (TEAC) was created to develop a new blueprint for the system. TEAC proposed that qualifications offered in the sector should be subject to what they called a “desirability test”, an assessment of match to national, strategic or commercial need. The government flirted with the idea; a set of “assessment of strategic relevance” reviews was run in the private training establishments and in 2003, the government included what they called a “strategic component” in the tuition funding framework (complementing what they called the student achievement component[2]). The trouble was, no one could work out how to operationalise the strategic component in a way that was appropriate, that would be transparent and fair, that was free of perverse incentives but that made realistic, defensible distinctions on a widely accepted definition of relevance (let alone strategic relevance). In short, who was going to make the call on how many graduates in (say) humanities we need? Or that we have “too many” graduates in humanities? And how could those judgements be made?

Or whether extra bonus funding for university departments teaching (say) engineering really would result in lots more 17-year-olds selecting engineering and if so, whether that would translate, four years later, into extra engineering graduates without causing a corresponding reduction in the number of graduates in (say) medicine or physics or IT. And with the strategic component funding tied to enrolments, would that be sufficient to generate anything more than a marginal increase in expertise in the university department – unlikely to be enough to realign the capability of the department to national needs.

Claiming to be strategic may have seemed like good politics. After all, it seemed like a repudiation of the much criticised “bums on seats” approach of the 1990s. But this was a classic case of good politics leading to poor policy ambition.

So, in the first few years of the new framework, tuition funding was allocated solely on the basis of the student achievement component (or SAC) and in 2006, the strategic component was quietly dropped altogether.

In fact, the more significant realignment of university capability was always more likely to come through the research funding system changes. The introduction of the PBRF and the CoREs incentivised universities to hire new researchers, creating the opportunity to extend the institution’s capability into emerging areas, with the potential for spin-offs for the reach of the teaching programme.

But we are not alone …

In Australia, the recent comprehensive strategic review of higher education – the Australian Universities Accord – called for something very similar. The Accord team devoted a large section of its report to the same topic – how to deliver skills that match the nation’s current and future needs[3]. Their analysis – and their proposals – were similar to TEAC’s. Some critics and commentators (notably Andrew Norton, professor of higher education policy at ANU) raised objections similar to those discussed above[4].

Australian cynicism of the Accord’s suggestion of a strategic dimension to funding allocations was likely heightened by the experience of the Australian Job-Ready Graduates scheme …. in 2021, a new higher education minister modified the funding system to favour fields that he considered strategically important. Under Job-Ready Graduates, government subsidy rates increased (and tuition fees decreased) in fields in which there were perceived skill shortages and that were reputedly employment rich. Conversely, in fields like humanities and social sciences, tuition fees rose markedly and government funding was cut sharply. This was a crude (and – predictably – unsuccessful) attempt to use price to push enrolments into what the minister thought were high relevance fields. Fees for humanities subjects went up by 117%, while fees for mathematics and statistics dropped by 59%. But the shift in enrolments was slight, only 1.5% across the whole system[5]. The response to the fee drop in mathematics and statistics was minuscule – around 0.05%, largely because once a student has made the decision to take higher education, the choice of field is mainly driven by interest and aptitude as well as by the wish to build the base for a career[6].

But in any case, the policy response needs to be more sophisticated than the naivety of the Job- Ready Graduates scheme. In a 2016 commentary entitled 18-year-olds or politicians: who makes the better course choices? Andrew Norton argued that evangelism for enrolments in STEM fields by ministers, by industrialists, by the science community had led to the observed increase in number of bachelors graduates in science which then led to a rise in the rate of unemployment among recent science graduates.

It is simply fallacious to believe that a need for more science-led innovation and for a more technology-led economy requires a population with a disproportionate numbers of science graduates; science-led innovation is built on the quality of science, working in a community that has the ability to nurture, translate and commercialise the science. Quality, not quantity. The loudest voices aren’t always right.

… which brings up one of several elephants in this small room …

- The university system is an important source of the skills that the nation needs. But, when it comes to meeting the labour market demand for a particular skillset, the supply of university graduates is only one factor. The second major factor is migration; NZ graduates leave the country on OE or in pursuit of opportunity while others enter the country with qualifications obtained elsewhere. The skills available to employers depend on patterns of migration – immigration and emigration – as much as on the education system. Plus … employers won’t be able to access the skills they want and need unless the conditions of work in the industry are favourable and attractive to those who have the skills and qualifications needed. And many of the best graduates will shun work in an industry that is poorly set up to provide the professional opportunities that are available to their peers in other countries.

- Matching is a complex matter; the university system can help provide the knowledge and skills the nation needs, but it usually won’t be able to solve the problem. Any supply-side intervention is likely to need to be complemented by demand-side actions.

… and another …

- The employment outcomes of NZ university graduates happen to be good, in all fields, humanities included[7].

Unemployment rates are negligible among young bachelors graduates five years out from study in all fields, so low that, in most fields, the data has to be suppressed for confidentiality reasons. That applies to traditional humanities fields, as well as to more vocationally oriented fields such as IT and accounting[8].

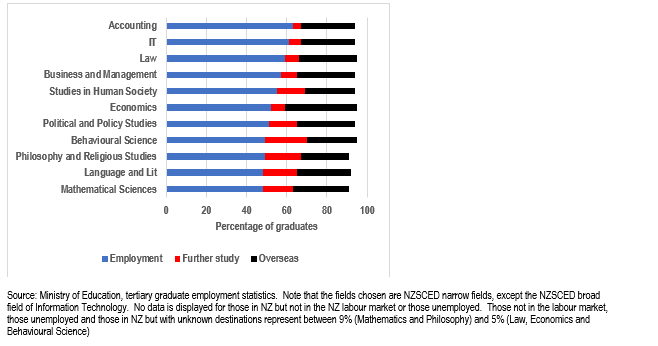

Figure 1 below looks at young bachelors graduates five years after graduation and reports on their principal destination – are they in employment, in further study or overseas? We report this for graduates who have majored in a group of fields – six arts degree majors plus some others as comparators.

Figure 1: Destinations of young bachelors graduates five years after degree completion, for selected fields of study.

While there is all but zero unemployment by field of study, there are differences in destinations. Graduates in vocationally-oriented fields – accounting, IT and law – are more likely to be in work. Economics graduates are most likely to be living overseas. Graduates in many of humanities/social sciences fields have the highest rates of return to study.

Likewise, when we look at earnings of bachelors graduates five years out from graduation, we see that traditional humanities fields like Language and Literature and Philosophy and Religious Studies) have relatively low medians. In part, it is likely that the high rate of transfer to higher level study among humanities graduates distorts the comparison; those with higher grades are less likely to seek work with a bachelors degree.

In short, the labour market does value all bachelors graduates, including those who majored in humanities.

… low demand fields ….

One of the important matters that arose when the financial constraints really hit the universities in 2023 was how to handle fields of study that were of importance, had low student uptake and were offered in more than one university across the country. Languages, agriculture and horticulture, some important cultural fields (like ancient history), some performance music …

The VCs of Otago and Victoria put their heads together. Could they somehow combine, share the students, share the costs of delivery, use online delivery in such a way that every student got some face-to-face, some online. It was a sensible pragmatic approach. But the diseconomies would – inevitably – remain. That’s another matter that the government might look at if it adopts my suggestion of a relook at the structure of the funding system for higher education.

| An anecdote In 2014, as the Ministry of Education was developing its approach to the analysis of institutions’ graduate employment outcomes data, I visited a number of institutions to discuss their preliminary results. At one institution (not a university), I pointed out to the CEO that one degree of the dozen or so offered at the institution had much poorer outcomes than all the others. The difference was striking. This was a degree in the performing arts. I asked for her comment. She told me that that degree was the most over-subscribed the institution offered. Three in every four qualified applicants was turned down. She told me that those applying for that degree were realistic. They all knew that there was a very low probability of continuous employment as a theatrical performer and even lower of stardom and high earnings. And that fact was reinforced to the applicants during the selection process. A small proportion did go on to successful careers in theatre with some TV/film work, but the majority ended up in casual employment between theatrical contracts, often in hospitality or the tourist industry (where successful tour guides often rely on their performance skills). Even knowing the odds, most were undeterred. That is a case of mismatch … an oversupply of graduates, yes. Evidently an oversupply of quality graduates, but an industry structure that sees most employers forced to offer low wages and to accept uncertain work flows and in which success is often the result of unreadable, unpredictable factors … with the mismatch compounded by the determination of so many to try their hand, knowing the chances of success were low. But who could with confidence identify the next star from the next gigging actor? As long as students understand the risks, who can decide which should not be free to make the risky choice. Careers information is important of course[9], but the dynamics of decision-making are complex. |

…. and yet another …

A 2022 US natural language processing study of millions of higher education course syllabi and millions and millions of academic papers was used to create an analysis of how well higher education practice[10] in 800 US universities equips graduates with the most up to date knowledge – with ”frontier knowledge”. The results show (predictably) wide variation, suggesting that instructor quality is important in ensuring that what universities teach is at the knowledge frontier – the instructors who are active in research tend to operate closer to the knowledge frontier in the discipline. According to the researchers, that difference can have implications for “… labour market outcomes, education choices and technological progress…”

That places an important responsibility on departmental leaders in universities to keep the courses offered in their department up to date.

Meaning …

One of the key conclusions from that discussion is that whatever any approach to improved matching looks like, it should be underpinned by student choice[11]. On balance, student choice of field of study reflects their interests and aptitudes as well as their aspirations. The research shows that a person who sees higher education as a possibility will take account of what influencers advise and their perception of career opportunities as well as their interests and strengths[12]. And that, if students succeed in higher education in whatever field they choose, wherever they study, they will have the base for good employment outcomes that will make a contribution to the labour market and to the economy[13].

Matching to national need needs to take place without compromising student choice.

A second take-out is that the universities’ internal quality processes and their instructor development practices can make a great deal of difference to whether graduates emerge with up-to-date knowledge and skills.

Which raises another important issue

The match of universities’ range of teaching and research to New Zealand’s needs relates only to one aspect of the university’s purpose – its role in human capital formation. That is a critical function of universities; it is the function that provides the most powerful justification for the very high level of public subsidy for the system, the function that provides much of the motivation of most students to enrol[14]. Ultimately, it’s what makes universities viable in countries like ours.

But it isn’t the sole function of a university. Theorists of higher education (like Simon Marginson, Professor of Higher Education at the University of Oxford) argue that in addition to its extrinsic role, the system also plays an intrinsic role for students, a role he describes as subjectification and socialisation, the process of helping individuals become autonomous decision-makers)[15].

I agree. There is a value, especially for young people, in the experience of study, in the interplay of the range of subjects of study, in the interactions with the people in the institution, other students as well as academics. It’s a rite of passage.

But that personal transformation is something that also (if incidentally) contributes to the graduate’s socio-emotional skills, helping people develop transferable cognitive skills (such as the ability to think independently, apply the ideas from one context in another, …) That has a labour market value too (if intangible).

It’s an important factor to keep in mind, but it doesn’t deflect from the matter under discussion – how universities meet the skill and knowledge needs of the society.

… and we need to remember statutory freedoms

The Act states[16] that institutions have the freedom to determine what they teach. A university can’t be compelled – not by government, not by anyone else – to offer teaching in a particular field or to structure its teaching in particular ways, no matter how sensible or foolish the decision might be. However, if a programme in a new or emerging field really is a national priority and if the university had or could find the expertise needed, then it would likely be in the university’s financial, as well as social, interests to do its utmost to offer it. NZ’s universities are autonomous, but they are also conscious of their rational role.

How to plan to meet the nation’s needs

It is clear that matching university system capability and expertise to national needs is inevitably complex. It’s a problem with three dimensions:

- forming a sophisticated understanding of the country’s needs for skills, knowledge and research in emerging fields

- translating that understanding into a response from the university system within the constraints and the funding system the universities operate under

- ensuring that universities’ research is at the knowledge frontier in the fields that are evolving rapidly and that matter nationally.

Understanding emerging needs

The matching problem is important for universities and for university system planners, but especially for government and for firms in the affected areas. The experience of the last 20 years suggests that we need to find new ways of understanding mismatches, better ways of using the resources of government, industries and educators to address problems. We need to avoid the simplistic thinking that suggests that any matching problem is a failure in the supply side and that it can be fixed through rearranging funding for universities.

The first step in addressing any matching issue is information, in developing an understanding of the issue. That needs objective, proactive, comprehensive monitoring leading to identification of areas of potential mismatch. Proactive, rather than in response to articulate advocates. Monitoring by labour market experts, by the skills agency, by migration analysts and by the education agencies. And where problems are identified, there’s a need for a deep investigation of the causes, leading to a nuanced understanding that can be translated into an intervention. It needs to recognise that matching problems will have different causes in the demand side, migration patterns and the supply side.

So the analysis needs to take account of:

- the influence in an industry of demand-side factors (like conditions of employment, remuneration, the reputation of the occupation …)

- migration factors (how many graduates take OE or emigrate, and how well that loss is matched by immigrants with similar qualifications, of similar quality, in similar fields)

- supply-side factors (where enrolments and completions in the appropriate qualifications are low or where the education system does not offer the field of study at the heart of the mismatch).

Only with an appreciation of the drivers can an appropriate (and effective) intervention be devised. Only with effective, proactive monitoring can the government’s response avoid capture by the loudest voices. Only then can we avoid simplistic supply-side responses to more complex demand-side problems. But where the mismatch can be traced to a supply-side problem, we can hope for a solution developed by government in cooperation with the industry and the higher education system.

An interesting case study is the successful E2E – education to engineering – project. In 2014, the TEC coordinated a project, involving tertiary education institutions and the engineering profession, to resolve a gap in the supply of professional engineers and engineering technologists, creating a partnership between the industry and the tertiary education departments, orchestrated by the TEC, using a systems integration approach[17].

When a demand field is not taught at all through the system, the problem is more complex. Currently, that mostly relies on the links between the industry and a university with expertise in a related discipline. If the university perceives it can take on the field with a manageable investment and make good returns, it likely will. That applies as much to over-subscribed, financially strong universities as to those that are struggling.

| Another anecdote In 1988, Lincoln University’s[18] horticulture department set out to complement its viticulture teaching with classes in oenology. They created a postgraduate diploma, building on their horticultural expertise, and drawing on their connections with models from North America and establishing close relations with local wine-makers. Plus adding a small number of extra instructional staff. The first comprehensive viticulture and oenology qualification in NZ, landing at a time when the industry was growing. Most of those who completed the diploma found employment in the industry and went on to successful careers in the industry, From that start, there was gradual expansion – of scale and of the university’s capability. It set the pattern for training in viticulture and oenology in New Zealand, based on the US model of research-led teaching complemented by practical experience leading to a credential, rather than the informal apprenticeship system that arose over centuries in some European countries. There are now many programmes in viticulture and oenology in NZ, and a much-expanded programme at Lincoln. What drove the success was the commitment and determination of the initiator (an associate professor in horticulture), his experiences in North America, his connections to the local industry and his realisation of the gap |

Matching in research

The question of what areas a university should research is subject to the requirement in the Education and Training Act, that most of the institution’s teaching is conducted by those active in research[19]. That means that a good proportion of the research will be in areas that are less valuable from a strategic or commercial perspective. And funding from the PBRF, the most important of the university research funding streams, is strengthened if there is more high-quality research produced in the university[20], meaning each university’s research output will cover multiple fields, some highly strategic, some less so. Plus, the PBRF is untargeted funding – the university decides how it spends the PBRF funding, allowing it to use the funding for multiple purposes, across the range of the university’s work.

That discussion leads to the conclusion that there are no command levers for government, business or community groups to pull. It means:

- If government, community groups, philanthropists or commercial interests want to reshape university research in a more strategic direction, it is necessary to fund it, either through existing competitive government funding streams or by contracting the university to do the research[21]

- The university leadership needs to ensure that each specialisation/ discipline/ field of research has good leadership.

On funding …

The government’s research funding streams are able to be shaped to emphasise themes that are seen as of national importance; they are periodically reshaped as priorities change. Businesses can gain tax credits when they commission an approved research provider[22] to undertake research on their behalf.

On research leadership

A good research leader in a university needs to be in touch with the trends in his/her field, needs to be familiar with (if not working at) the knowledge frontier in the field and needs to be alert to the potential for new research in the field to offer value for industry, for government or for community groups. A good research leader will build and maintain personal contacts with important decision-makers in industry or government and will have established relationships with similar departments overseas. A good research leader will understand the quality, value and timeliness requirements of research funders.

Essentially, it’s down to the universities themselves to manage the quality of the research leadership, and hence, their ability to support the production of nationally important research. If a university gets research leadership in a field wrong, it will see its competitors – domestic or international – win out.

Endnotes

References in the endnotes can be found in the bibliography for this series.

[1] Among the many references that establish this connection in different contexts from different perspectives are: Atkinson and Blanpied (2007), Feingold (1999), Kim et al (2012), Liik et al (2014) and Hanushek and Wößmann (2021)

[2] “… what was called the student achievement component ….” It was nothing of the sort, of course; it was a pure volume measure, with no achievement element, but named in a way that disguised its equivalence to the widely derided “EFTS-based funding system”.

[3] O’Kane et al (2024)

[4] See Norton (2023a). Norton repeated and extended this analysis in several posts on his Higher Education Commentary from Carltonsite.

[5] Yong et al (2023)

[6] Papers that explore this matter include Leach and Zepke (2005), James (2000), James et al (1999), Hofer et al (2020) and Volperhurst et al (2020). Yong et al (2023) focuses on how the ability to borrow fees from a loan scheme reduces the elasticity of demand for tertiary education to the point where price scarcely matters.

[7] See Smyth (2023e) for data and a fuller discussion of this matter.

[8] Refer to the data on tertiary graduate employment and tertiary graduate earnings on this page

[9] Hofer et al (2020)

[10] Biasi and Ma (2022)

[11] For an account of the risks of not using student choice, see pp 199-201 of Hrzynski et al (2018)

[12] Hofer et al (2020)

[13] Smyth (2018)

[14] Norton (2020), Leach and Zepke (2005), James (2000), James et al (1999), Hofer et al (2020) and Volperhurst et al (2020).

[15] Marginson (2023)

[16] At Section 267(4)

[17] See Vaughan (2018) for an evaluation of the E2E programme and a detailed description of its approach.

[18] Then called Lincoln College

[19] This requirement and its value are discussed in the Improving Research section of this submission.

[20] The question of the shape of the PBRF is discussed in the Improving Research section of this submission.

[21] Another avenue for community groups is to identify areas for research and offer to provide access to records, files or archives and to offer non-financial research support.

[22] All eight universities are on the approved providers list.