A submission in response to Number 17 of the University Advisory Group’s questions

| Executive summary The TEC/Ministry of Education relationship While the Ministry of Education develops policy advice on tertiary education, the Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) is responsible for implementing tertiary education policies – developing operational policy, allocating funding to institutions and monitoring the performance of tertiary education organisations. For the last decade, the two agencies have worked together, making sure that the advice to government meets government’s strategic objectives and also leads to decisions that can be implemented effectively. The relationship has worked well. Both agencies have done good work. While it would have been possible to configure the agency roles differently, the costs and risks of a major change would outstrip any possible gain. The UAG should recommend to government that the agency tertiary education roles and responsibilities should be unchanged. Data, analysis, monitoring, evaluation Policy advice needs to be informed by data and analysis. Both the Ministry and the TEC have done very good work in analysis and monitoring. The Ministry has been active in meeting the needs of ministers and policy analysts and in disseminating findings. But the agencies’ analytical resources are relatively thin and important exploratory analysis gets crowded out. More evaluative analytical resources would produce a richer information set that would strengthen advice to ministers and provide greater accountability information on the system. The UAG should recommend that government look to increase the agencies’ analytical resources. Quality assurance Universities NZ (UNZ) has the statutory role for quality assurance in the universities. As the system grows and as the student body becomes more diverse, quality assurance assumes a greater importance in the system. The collegial approach to programme approval (through the Committee on University Programmes) has a focus on improving teaching and learning and supporting each university’s internal quality assurance, rather than accountability. This works well. The quality audit process run by AQA complements other quality mechanisms, providing an independent perspective on universities’ quality systems. The recent decision to disestablish the arm’s length relationship between UNZ and the board of AQA and to bring academic audit into the UNZ secretariat risks being seen as compromising the independence of audit. The UAG should advise UNZ of the risks of removing the arm’s length relationship between itself and AQA. Agency roles in policy advice on research and science and innovation University research has to fulfil an educational role, as well as contributing to the strategic and commercial goals that drive policy in the national science and innovation system. Some tertiary education research funding (especially the PBRF) is designed to be used on priorities set by universities (rather than by government or commercial interests). However, a part of the university research effort is in tune with the national science system. Part of the tertiary education research funding system incentivises universities to meet strategic and commercial goals. That difference in research purpose justifies the separation of research policy advice, with MBIE providing advice on the national innovation system and the Ministry of Education responsible for advice on university research. The two agencies need to communicate and work together as needed. The UAG should recommend to government that the agency roles on policy advice on research should be unchanged, but MBIE and the Ministry of Education and TEC should be encouraged to strengthen their collaboration on research policy, on research performance analysis and monitoring. Agency roles in skills policy and analysis The monitoring of skills matching requires three perspectives – labour market, migration and tertiary education. It was noted in the matching section of this submission that the best way to do this is to involve policy analysts and information analysts representing all three perspectives and to establish a pro-active monitoring regime. That regime should involve information and policy analysts from MBIE, the Ministry of Education, and the TEC and it needs to have clear ministerial and public reporting obligations. |

| Disclaimer In commenting on agency arrangements, I need to point out that between 2002 and 2017, I was employed in the tertiary education group of the Ministry of Education, that I set up the Ministry’s tertiary education monitoring and analysis team, that I led that team for more than a decade and that I was the tertiary education policy group manager for four years. That experience has given me particular insights into the topic and has shaped my assessment, but has not, I trust, compromised my judgement. |

Context: the agency picture

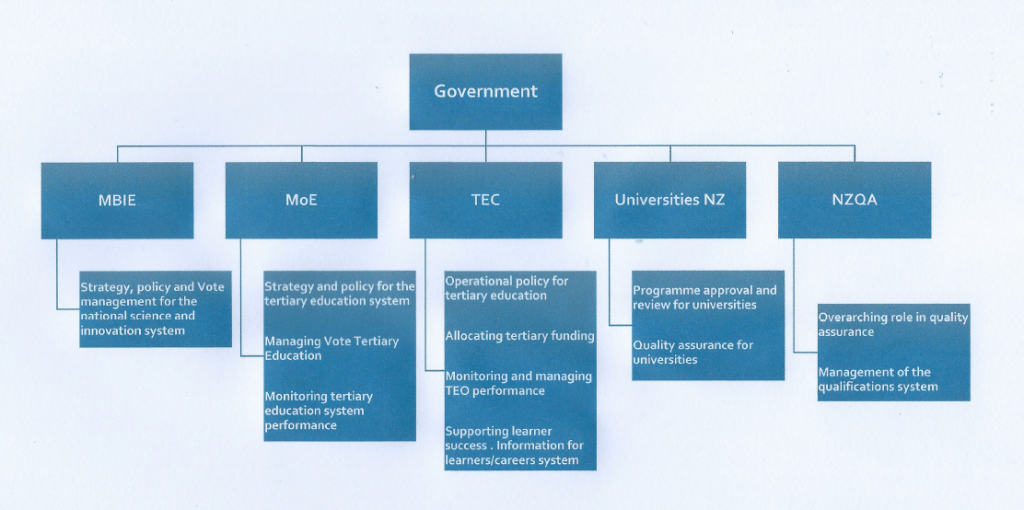

In New Zealand, there are several government agencies with a role in advising on, managing and overseeing the tertiary education system. It is not possible to think about the policy setting arrangements without referencing the whole array of agencies.

Figure 1: Government bodies and statutory entities with a role in managing the New Zealand tertiary education system

In this submission, I discuss the agency arrangements as a whole and indicate where there needs to be change and also review the arrangements for policy advice on the science and research system.

The relationships between the Ministry of Education and the Tertiary Education Commission

Background – the status of the TEC

The Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) was set up following a recommendation from the Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (TEAC) – the body set up in 2000 to conduct a major review of the policy settings for tertiary education[1]. TEAC saw the TEC as a system coordination body. TEAC wanted the TEC to be independent of government but also to have a role in policy advice and in developing system strategy[2].

That is not what happened. The government decided (in 2003) that policy advice should be provided to the minister by the Ministry of Education[3], not the TEC. The TEC was set up as a Crown agent, meaning it is required to give effect to policy. Its role is to create operational policy to give effect to the government’s policy decisions[4]. The TEC divides up the government’s funding allocations among institutions. It also monitors the performance of the providers of funded post-secondary education. It’s an important role, but it’s not a strategic role.

It’s easy to see the dilemma posed by the TEAC vision for the TEC; few governments would want to delegate policy-making rights in a strategically critical, potentially contentious area (such as tertiary education) to an arm’s-length, quasi-autonomous body. Ministers face electoral accountability; independent leaders don’t[5].

The TEC role

The government’s decision on the roles of the Ministry and the TEC posed a challenge.

In most portfolios, the policy advice function and the policy implementation role are contained within a single agency; the boundaries between the two are permeable and any tensions are invisible outside the agency. However, when the policy and implementation roles are held in different agencies, the permeability is less. This means the relationship between the two agencies is important to the effectiveness of the policy process.

The agencies have developed a structured relationship for defining the parameters under which TEC can act. After a somewhat rocky start, that relationship appears to have worked very well for the last decade or more. While the Ministry is responsible for the advice on policy, it works with the TEC during the development phase to ensure that the advice to the Minister delivers policy that is able to be implemented efficiently, and in the way intended.

Both agencies do good work[6]. The TEC does excellent work within its role. One example is its Ōritetanga Learner Success programme, which supports and encourages TEOs to find ways of lifting student success and of reducing disparities in achievement in tertiary education. Another is the way it monitors and supports the organisational and financial performance of TEOs. And it assesses TEO plans and delivers funding efficiently.

However, the TEC’s role means that the role of the commissioners is mostly as governors of the organisation; they don’t play the system strategic leadership role envisaged by TEAC[7].

Data, analysis, monitoring, evaluation …

Both the TEC and the Ministry have a responsibility for analysing data on the performance of tertiary education organisations (TEOs) and of the system[8]. The TEC has a particular interest in the analysis of and research into the effectiveness of teaching and the performance of funded TEOs. The Ministry is vitally concerned with the analysis of system settings. Both are concerned with outcomes – labour market outcomes but also non-economic outcomes.

Both agencies have done excellent work in this role, the Ministry especially. There are many examples of this excellent work – for instance: the development of employment outcomes information, the evaluative monitoring of the Youth Guarantee programme, of the fees-free programme, of the results of the PBRF quality evaluations, of the CoREs and of progress towards the achievement of Tertiary Education Strategy targets. As well, there is reporting on institutional financial performance and reports on the forecast enrolments. And reporting on the value for money delivered by major funding streams. Plus identification of factors that influence participation and success in tertiary education. The agencies were pioneers in the use of the IDI and continue to make extensive use of the IDI. The publicly available information paints a rich picture of the performance of the system, of particular policies and of institutions[9].

However, ministers are typically hungry for the data and for information to underpin their decisions; they rightly expect agencies to satisfy that hunger. Policy analysts also need data and evaluative analysis to shape their advice. Those needs create heavy demands on the two agencies’ monitoring and analysis teams, stretching the relatively thin analysis resources and often crowding out exploratory work. Many series – for instance, the valuable value for money series, the analysis of outcomes, the analysis of the performance of foundation programmes – have lapsed, while others (such as the deeper population studies) have become sporadic. The IDI has been strengthened and enriched so many of the earlier IDI-based analyses cry out for updating. This is not a criticism; analysts must always prioritise pressing requests. The upshot is that the publication of evaluative material is less than it might be.

In an ideal world, ministers, agency managers, analysts and advisors, the sector, interested observers, the public, the news media would all see evaluative analysis of the performance of all major programmes on a regular basis. In an ideal world, the agencies would be more proactive and more comprehensive in their analytical programmes. In an ideal world, all decisions on the direction of the system would be underpinned by that comprehensive analytical work[10].

That would need further investment and more analysts but it’s an investment that would repay in better policy and in more effective targeting of funding.

Overall

In the wake of the TEAC report, it would have been possible for the government to have created other configurations of responsibilities and other agency arrangements (for instance, the sort of departmental agency arrangement now being mooted for the soon-to-be-created Australian Tertiary Education Commission). There were tensions in the initial years between the TEC and the Ministry of Education, but with stronger ministerial direction, with excellent leadership and greater role clarity at the TEC, those tensions have eased. With the Ministry and TEC now working together well, there is no benefit (and very considerable risk) from making changes.

However, if the agencies could employ more information analysts, they would be able to undertake deeper, ongoing, proactive monitoring of the performance of the system in all of its main outcome areas, give a deeper understanding of how the system works with and for different population groups, how the student support system is working ….. They could produce a richer set of information resources that would strengthen advice to ministers and provide greater accountability information to the sector and the public[11].

Quality assurance

The approach to quality assurance in the universities has its origins in the break-up of the University of New Zealand in 1961 and the creation of the University Grants Committee (UGC). The UGC’s curriculum subcommittee – comprising one VC as chair and a senior academic leader from each of the universities – operated a collegial programme approval process; proposed new qualifications and proposed major changes to an existing qualification were reviewed, assessed, modified (if necessary) and (usually) approved by the delegates of the universities.

When the Learning for Life reforms were being debated in 1989, the universities told the government that universities in most Commonwealth jurisdictions (including Australia and the UK) were “self-accrediting”. They stated that the universities wanted to maintain collegial and collaborative programme approval (rather than be self-accrediting), and therefore, it was unnecessary to give the planned new quality and regulatory agency – what became NZQA – the responsibility for, and the right to conduct, quality assurance in universities. The government agreed to that case; as a result, the NZ Vice-chancellors Committee (now called Universities NZ) was re-established as a statutory organisation and given quality assurance responsibilities in legislation. This led to the rebirth of the UGC curriculum subcommittee as the Committee on University Academic Programmes (CUAP), a body that built on the collaborative approval processes used by the UGC curriculum subcommittee and extended them – including, for instance, graduating year reviews.

While NZQA does not have responsibility for quality assurance in universities, it is responsible for regulating the post-secondary education qualifications system[12]; CUAP works to a set of rules promulgated by NZQA as part of its regulatory role.

CUAP does not see its quality assurance as an accountability mechanism; rather, it is positioned as a body that offers expert improvement advice[13], reinforcing the internal quality processes that universities operate.

Strong quality assurance is seen as one of the pre-requisites for expanding access to higher education[14]. Therefore, in 1992, with enrolments in British higher education having grown in response to government initiatives, the UK universities established the Higher Education Quality Council (HEQC) that conducted independent external quality audit and quality assessment[15]; in effect, that qualified UK universities’ right to manage their own quality internally, their status as self-accrediting institutions.

Reflecting the British experience, Universities NZ created the Academic Quality Agency (AQA, formerly called the NZ Universities Academic Audit Unit) in 1993 to conduct institutional quality audits, akin to those developed and conducted by the HEQC in the UK, complementing the work of CUAP and providing a measure of external accountability while still maintaining a focus on constructive improvement advice.

The AQA, while owned by Universities NZ, is governed by a board that is at arm’s length from Universities NZ; its register of academic auditors are mostly (current or former) senior academics, or senior tertiary education managers[16]. AQA’s arrangements strike a balance between independence and expertise[17].

However, in June 2024, UNZ announced its intention to disestablish AQA as a quasi-independent, arm’s length body. UNZ plans to retain the audit principles and processes developed and used by AQA but to manage academic audit through the UNZ secretariat. Given the value that AQA has created and the credibility it has built over its 30 years, the loss of the arm’s length relationship between audit and UNZ poses a credibility risk. It’s not that the process would necessarily be any less rigorous; rather, the risk is that it would reopen old arguments about the independence of university quality assurance and about accountability for quality.

Overall

In 1990, sceptics argued that the NZ university system was too small to run a credible quality assurance system; it wasn’t possible, critics claimed, to achieve independence in so small a system. However, the combination of collegial programme approval through CUAP and an arm’s length quality audit system appears to have worked well in practice; this combination maintains the focus on improvement and reinforces the universities’ internal quality processes while providing a measure of independence and accountability. There is, however, a question mark over the decision to disestablish AQA as a distinct entity, with a board and a register of auditors that are both “of” and “independent of” the university system.

Research, science and innovation policy

There are important differences between the role of the Ministry of Education and MBIE in research and science policy.

MBIE’s role is to advise government on policy for the national research, science and innovation system, and to create operational policy, to manage the Votes that cover science and innovation and to administer and oversee the government’s public good research and science funds.

That work has an important impact on the university system. The universities are major contributors to the research system and major recipients of government research and science funding, they house most of the country’s researchers and they are responsible for much of the country’s research output. Therefore, MBIE’s policy advice and administration of the national science system affect (and are affected by) universities’ work. University research revenue also benefits from the science funds that MBIE manages or oversees.

But, under the law, universities have a broader research role than that covered by the national science system. Whereas the national science system, funded by the votes managed by MBIE, is concerned with advancing the country’s strategic interests in research and science, the role of the universities in research (as set out in s268 of the Education and Training Act 2020) is broader.

University research is to be interwoven with teaching, so university research has an educational purpose, not only a strategic purpose. And the requirement that most academics undertake research means that some research will cover fields that could be interpreted by MBIE analysts as lacking strategic or economic importance. Finally, much of the research funding provided through Vote Tertiary Education is untagged and applied at the discretion of the university management or academics; it is investigator-led, much of it blue-skies research. In most universities, research doesn’t actually generate enough revenue to cover its costs[18].

Alongside investigator-led research, the tertiary education research system does allow for and does encourage university researchers to be active in commercially-focused research, in strategic public good research and other research that meets the goals of the national science and innovation system. The external research income (ERI) component of the PBRF has been designed specifically to create incentives for universities to work in those areas while maintaining the educational focus of their research programme as a whole.

Those features, essential characteristics of university research programmes, mean that there is a substantial difference in goals and culture between MBIE-funded research and research funded through Vote Tertiary Education. While much university research is well-aligned to national science and innovation priorities, not all university research will be.

The Ministry of Education, with its responsibility for advice on tertiary education policy (including all aspects of higher education policy, as well as policy on vocational and foundation education), is best placed to advise on how university research is funded and incentivised and on how it fits with universities’ other roles. Universities need to (and currently do) keep a foot in each camp. That analysis suggests that the current split of roles is appropriate.

However, that split places a responsibility on the two agencies to ensure they understand and appreciate the differences and also the synergy between the two – it’s a matter of creating mechanisms to build, deepen and maintain dialogue between the two ministries.

Research is not the only MBIE policy responsibility that affects and is affected by higher education. MBIE is also responsible for skills policy (while the university system is a major provider of the skills that the workforce needs) and for migration policy (which also intersects with tertiary education – not only in the universities’ work in international education, but also in skill loss through emigration). The Ministry of Education has also worked closely with MBIE in these policy areas.

Overall

The cost and risks of any change in the government agency arrangements for research, science and innovation policy would outweigh any possible gains.

However, the agencies should be encouraged to strengthen their collaboration on research policy and also on the monitoring and analysis of research performance.

Skills policy and monitoring

In the section of this submission that covered how the universities can meet national needs in teaching and research, I discussed how we need a better understanding of skill matching – how the education and migration systems jointly contribute to a supply of skills that are demanded by the labour market. A proactive analysis of trends, field by field, occupational group by occupational group.

I pointed out that we have a need for greater coordination in monitoring skills gaps. That’s a matter that can’t be dealt with by MBIE’s skills/labour market and migration divisions alone. The third part of the puzzle is the tertiary education perspective – which needs to come from the TEC and the Ministry of Education. To be effective, that will need both a policy perspective and a data, monitoring, and analysis perspective.

That will place yet more pressure on the already stretched Ministry analysis team, possibly also the TEC.

Endnotes

The endnotes below refer to the readings and research that have informed the analysis and arguments in this paper. The full bibliography is at this link.

[1] See Boston (2002), Smyth (2012), Smyth (2023c and d). For background on the reasons the government commissioned the TEAC review, see Roberts and Peters (1999).

[2] See Boston (2002)

[3] Section 253, Education and Training Act 2020

[4] Sections 400, 409, Education and Training Act 2020. Note that section 416 prohibits the Minister from issuing a funding determination that directs the TEC to fund or to not fund any specified organisation.

[5] The same debate was played out in Australia in 2023/24 when the Accord review proposed a tertiary education commission, independent of government, that would have wide strategic and policy powers. See Smyth (2023a and b).

[6] It might be worth noting that in his memoir I’ve been thinking, a former tertiary education minister, Hon Steven Joyce described his expectations of policy advice on taking up the portfolio: “I wanted much more analytical rigour, and conclusions and recommendations drawn from the data, not the other way round … After the first sixth months, the advice from the ministry was some of the highest quality I received as a minister …’

[7] Interestingly, the Australian government plans to establish the Australian Tertiary Education Commission, proposed by the Accord, as a “statutory office” within the Department of Education. That appears to be what in NZ is called a “departmental agency”, like the Ministry for Ethnic Communities (which sits within DIA but has direct reporting to its own minister). The details of the new funding legislation have not yet been revealed (and hence, the precise responsibilities of the commission. However, it appears that this structure is intended as a mechanism for enabling the four commissioners – one of whom will be full-time – to enjoy a greater strategic role than the NZ tertiary education commissioners have.

[8] TEC’s role derives from Section 409(1)(b) of the Education and Training Act 2020. The Ministry’s role is implicit in Section 253; that section makes the Ministry the principal policy advice agency, a role that must be underpinned by monitoring evidence, evaluative analysis and forecasting information.

[9] See Education Counts and the TEC website for examples. Note that some of those analytical series are extended only sporadically – for instance, the value-for-money series, the deep analysis of foundation education, the monitoring of the progress against the goals of the Tertiary Education Strategy…. The base is there; it needs to be kept moving.

[10] One of the important themes that emerged in the Australian Accord process was the need for better data analysis, measurement of progress and ongoing evaluation – see the Accord Final Report, pp 251-254.

[11] Note the complementary recommendation about research into teaching effectiveness in the Improving Teaching section of this submission.

[12] Sections 452, 453 and 439, 440 of the Education and Training Act 2020.

[13] See Houston and Paewai (2013). That paper discusses the differences between the accountability and improvement purposes of higher education quality assurance, drawing from a NZ case study. The authors argue that accountability-focused systems are “… unable to contribute to the improvement of teaching and research in the university”.

[14] See UUK (2008) pp 17-18

[15] Quality audit = checking the university had the systems that enabled it to manage its quality appropriately. Quality assessment = an independent assessment of how well teaching was being conducted. The system was later simplified and the HEQC was replaced by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. See UUK (2008).

[16] Refer to the AQA website.

[17] See Matear (2018) for an example of the findings of an audit cycle.

[18] The PBRF in particular. See also Norton and Cherastidtham (2015) for an Australian view of how research costs are supported by teaching.