My response …

Here is my response to the third round of submissions to the UAG. To keep within the page limit, I have addressed only three of their questions, those that ask for suggestions of alternatives to the PBRF, the question of how much students should pay and how the funding system should ensure the supply of graduates in important fields – questions 8, 7, and 4 of the call for responses.

Q8 How could the Performance-Based Research Fund (PBRF) best support a continued focus on research excellence, while minimising compliance costs and any other unintended consequences?

The four reviews of the PBRF held to date have all reaffirmed that the research quality evaluation (QE) should be at the level of the individual academic, with those individual assessments aggregated up to produce an institutional rating. There is wide agreement that part of the reason for the transformation in university research culture over the last 20 years is that the PBRF assessment has been of the individual academics’ research performance; individual academics strive to demonstrate their merit.

Analysis by Universities Norway suggests that assessing research performance at the individual level means that peer review is the most reliable means of evaluating quality. But, at national and institutional levels, quantitative measures are more useful – see Figure 1. So metrics are more valuable for institutional assessment but are not suitable for assessing individuals …

But peer review is time-consuming and labour-intensive. And Tim Fowler, CEO of the TEC, told the Education and Science Select Committee in February 2024 that the gains from another QE round would be “marginal”.

The question for the UAG is whether it is prepared to recommend a shift from an effective but costly, time-consuming (and deeply unpopular) individual peer assessment to a system at the institutional level that makes greater use of metrics.

Furthermore, while peer review underpins nearly all assessment of research – it is used to decide what gets published – the evidence is mixed on the effectiveness of peer review as a means of assuring quality. Peer review may be good at identifying weak items, but reviewers struggle to agree on the ranking of research papers …[6]

Given the doubts about peer review, given Tim Fowler’s view about the value of another QE, given the cost to government (and also to universities) of the QE, given the cancellation/ postponement of the next QE given the fiscal constraints surrounding the government’s work programme (and hence, the UAG’s proposals), …. in those circumstances, it’s important to explore the alternatives.

In an earlier paper (available here) I set out a possible approach to reconstructing the PBRF in a way that would be low compliance, that would build on the gains made in university research culture through the PBRF, that would take account of the practices of other countries and of research on the assessment of research, and that would recognise and reward the outcomes the system seeks from university research.

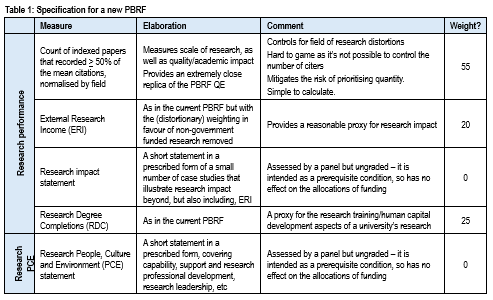

Table 1 summarises the broad outline I suggested in that earlier paper.

In looking at Table 1, the UAG should note:

- RDC and ERI are existing PBRF measures, with one small change proposed to the ERI formula.

- Analysis of the count of papers in the top 50% of papers in their field for citations shows that this measure predicted the last QE results well.

- The Research Impact statement and the People Culture Environment statement would be independently reviewed (for accuracy and appropriateness) and passed (or not) as acceptable.

- Applying a zero weighting to the two statements means that these would be prerequisite components; they would still be effective in encouraging institutions to work towards the outcomes we seek from university research because reputation is a powerful motivator of university behaviour.

- People, Culture and Environment has been adopted in the UK Research Excellence Framework in part because it’s a leading indicator; it tells us whether an institution has paid attention to building an environment that will foster excellent research in the next period (whereas all the other measures assess performance in the recent past).

Faced with this proposal, critics may be concerned that a bibliometric measure won’t capture the breadth of a university’s research. That is so. But the function of a performance-linked funding system is simply to gain a robust proxy measure of institutional performance – it is up to the institution’s management to recognise and foster individuals’ performance and to recognise creative work in fields not covered by bibliometrics.

Critics may ask “What about the wānanga? What about the polytechnics?” The government owes it to those institutions to find a different way of recognising and fostering their research without subjecting them to the stresses and indignities of a system designed for universities – as has happened for the 20 years of the PBRF.

This may seem a radical proposal. I suggest the UAG read the full argument in support of this approach, in which I explore the issues in greater depth and provide a fuller justification for each element.

Q7 Does the current system have the right balance of public (tuition subsidies) and private (student fees) contributions to the cost of university education, and what changes should be considered to tuition fee arrangements for domestic students?

There are three issues to consider in Question 7.

- Government tertiary education funding (and especially, university funding) is almost always regressive – it shifts resources from low-income groups to those in high-income groups.

- The planned new fees free mechanism, like its predecessor (first year fees free) is an extremely low value spend – egregiously so

- The student allowances scheme is poorly designed and fails entirely in its goal of increasing access to tertiary education by disadvantaged groups.

1 University funding is regressive because research shows the most important driver of university participation is school performance, and school performance is better among higher socio-economic communities. Analysis of the distribution of government transfers shows that nearly all social interventions are progressive in that they transfer resources to lower income families; tertiary education funding is the notable exception.

Yet university education confers considerable financial (and other) benefits on those who succeed in their studies.

Further, the presence of highly subsidised student loans on very favourable terms means that the price elasticity of demand for tertiary education is all but zero.

And it’s important to note that in 2022 and 2023, fee increases were limited to 1.7% and 2.75% respectively, in a period that saw cost inflation of 14%. So fees have dropped in real terms in recent years.

That combination of factors provides a case for a shift in the split of costs between students and government – for an increase in fees. At a minimum, restore the balance between students and government lost through 2021-2023. But, ideally, the fee increase should be higher.

2 Fees free: The previous government’s first year fees free policy performed in practice just as the research suggested it would. There was precisely zero impact on participation. Spending on the scheme was entirely dead weight. The current government’s planned final year fees free is equally – perhaps even more – ill-conceived. Given the high take-up of loans to pay university fees, these fees free schemes confer zero financial benefit on a student until he/she has completed studies, entered the workforce and is repaying – that is, until he/she is earning and in a relatively sound financial position. In other words, fees free gives a financial advantage only in speeding up loan repayment (which occurs, on average, six years[7] after leaving study). In other words, fees free delays any actual financial relief to the point when financial relief is not needed!

There is one group who do receive a genuine advantage from fees free – those who go overseas. That is because, under the loan scheme repayment regime, the repayment obligation of overseas-based borrowers is determined by their loan balance, not by their income; someone who received fees free would – all else equal – have a lower loan balance on leaving the country.

Fees free is an egregiously low value, deadweight spend. Fees free should be scrapped. The sooner the better.

3 Student allowances: The effect of student allowances is to cash up the living cost component of the Student Loan Scheme for young students from families with average to below average incomes. The scheme’s ostensible goal is to mitigate the risk that borrowing may deter people with straightened financial situations from entering into or persisting with tertiary education.

But the allowances scheme does not do any such thing. Those who receive allowances enjoy, by design, exactly the same government income support as those who don’t get allowances. And the consensus in the research literature is that family income plays only a minor role in the education decision making; factors like social capital, parental education and school achievement trump family income. The research finds that interventions early in life and that are sustained through childhood are most effective in supporting people at risk into higher education[8].

A rational government that wants to remove barriers to access and participation would scrap the student allowances scheme (except for students with dependent children) and would design an entirely new scheme that would involve targeting, mentoring and supporting young people in the years leading up to the decision to enrol. The current scheme is both far too generous (it supports people who don’t need it and who would be just as well off on the loan scheme) and not nearly generous enough (it ignores nearly all of those who could benefit from the extra support and it doesn’t offer the type and level of support that would be effective).

These three proposals would be controversial. However, the “rightness” of this analysis suggests that the UAG should include them in its advice, even if it would require a brave government to go there.

Q4 How can university funding be more responsive to changing enrolment levels and delivery models and ensure universities are responsive to current and future skills needs?

This response covers the issue of how the system meets national skill needs – a topic that inevitably arises in every strategic review of every tertiary education system everywhere. It summarises a paper I developed on the issue in response to the corresponding question in the UAG’s Round 2 call for submissions.

The question of responding to national skill needs is a matching issue, not simply a supply problem; adjusting the funding system to encourage universities to offer more of X or less of Y addresses only the supply side, not the whole problem. Adjusting settings to encourage more students to study X or fewer to study Y is also fraught with problems – when we want to meet a skill need, we need not simply quantity, we need graduates of quality who relish working in that field.

NZ has a poor record in responding to matching problems. Partly this is because the education system is only one source of the skills that the nation needs; migration is also a factor. Emigration and immigration. Partly, it’s because, in the absence of a systematic mechanism for proactively identifying emerging shortages, we are too often captured by lobbyists with the loudest voices. In a 2016 commentary entitled 18-year-olds or politicians: who makes the better course choices? Andrew Norton, professor of higher education policy at ANU, argued that evangelism for enrolments in STEM fields by ministers, by industrialists, by the science community had led to an increase in number of bachelors graduates in science which then led to a rise in the rate of unemployment among recent science graduates.

It is simply fallacious to believe that a need for more science-led innovation and for a more technology-led economy requires a population with a disproportionate numbers of science graduates; science-led innovation is built on the quality of science, working in a community that has the ability to nurture, translate and commercialise the science. Quality, not quantity. The loudest voices aren’t always right.

The key take-outs are:

- The tuition funding system in our universities should be underpinned by student choice; students do best – academically and in the labour market – when they take the subjects that interest and motivate them. We need to trust the universities to deliver the generic skills of analysis, communication, problem-solving … that make all our graduates valuable participants in the labour market

- Subject-based differentials in the funding system should be cost-based, not driven by views about the relative “strategic value” of subjects – the Australian Job Ready Graduates scheme provides an object lesson in how not to design a funding system[9].

We are right to be concerned about matching. But the way to resolve the issue is not through the funding system. It needs systematic objective, proactive monitoring to identify areas of potential mismatch. Monitoring by labour market experts, by the skills agency, by migration analysts and by the education agencies. And where problems are identified, we need sophisticated investigation … leading to a nuanced understanding that can be translated into an intervention. It needs to recognise that matching problems will have different causes in the demand side, migration patterns and the supply side.

As for the funding system … the UAG should be wary of piecemeal interventions and fixes (such as implicit in Questions 3-6 of the call for responses – we need a principles-based, systemic approach – such as laid out in this paper.

Endnotes

[6] This article discusses the evidence on the strengths and weaknesses of peer review. Defenders of peer review in this kind of system agree that it is flawed but many argue that it is the least worst system – see Wilsdon et al (2015), Stern (2016) and Wouters et al (2015)

[7] See the data on this page.

[8] See this paper which summarises the evidence and this which discusses alternative approaches for the allowances spend. See also: Cunha and Heckman (2007) The technology of skill formation NBER.

[9] See for instance: Yong et al (2023) University fees, subsidies and field of study Melbourne Institute and Norton (2023) Job-ready Graduates 2.0: The Universities Accord and centralised control of universities and courses Centre for Independen