“Is the BA dying?” asked the cover of the NZ Listener of 3 June.

Inside, in a story with the catchy title Arts and Minds, journalist Paul Little laments the way our universities have moved away from degrees in English, in the humanities and in the arts. Paul doesn’t trouble himself too much with the data[1], instead relying mostly on the anguished comments of academics from arts faculties – several of whom were quick to attribute the BA problem to the advent of higher tuition fees in 1990 and to the enduring cultural legacy of the governments of 1984 to 1993.

The Listener story also refers to an article with a similar theme in the New York Times. Paul might have referred (but didn’t) to many other similar views from other countries – for instance, recent reports from the British Academy and the Royal Historical Society on the decline of university enrolments in the UK in English and History. Or to the two reports from the Higher Education Policy Institute on the challenges facing the humanities in British universities. Or to the data on trends in field of study in Canadian and Australian tertiary education ….. or to data from any one of a number of other Anglosphere countries.

So, is it really true that the arts subjects are in decline NZ’s tertiary education system? If so, which arts subjects are particularly suffering? How does this compare with other countries? And if arts subjects really are in trouble in our universities, why has this occurred? Is it really true (as implied by those interviewed for the Listener article) that it is all the result of the change in public sector culture since 1984? Don’t BA graduates get jobs? What about the research produced by our universities in arts subjects? And how will this play out as universities attempt to deal with their current financial challenges and as some look to shed staff? How will the new funding announced by the government change things?

Important questions that Paul Little’s Listener article doesn’t really deal with.

What the NZ data shows …

In 2018, the Ministry of Education’s Warren Smart produced two reports on trends in field of study between 2008 and 2016. One (What are they doing?) focused on what fields domestic students study and the other (What did they do?) on the fields that domestic graduates specialised in. Warren looked first at broad fields of study and then dug into a few selected narrow fields[2].

Looking at enrolments in bachelors degrees or higher between 2008 and 2016, Society and Culture was the largest of the 12 broad fields of study. However, over the period 2008 to 2016, Society and Culture declined from a 32% share of degree level enrolments to 29%. Over that time, Health grew by three percentage points and Management and Commerce, the third largest broad field, declined by three percentage points (21% to 18%).

One of the focus areas for the Listener article was English, which is part of the narrow field Language and Literature (which is a part of the Society and Culture broad field). Warren’s analysis shows that bachelors level enrolments in Language and Literature were 7.2% of the whole in 2008 but had fallen to 5.3% by 2016. Language and Literature was one of the fields that was shown in Warren’s analysis to have declined most.

Consistent with the alarm expressed in Paul Little’s Listener article….

But that doesn’t quite answer the question about whether the BA is on life support

Arts degrees cover two main subject groups – humanities and social sciences. But the national subject classification system (called NZSCED[3]) doesn’t include the terms “Humanities”, “Arts” or “Social Sciences”. The NZSCED broad field Society and Culture field includes sociology, psychology, history, Te Reo, English, foreign languages, philosophy – all standard BA subjects. But it also includes law and recreation and sports (which are not arts subjects) and it excludes education, theatre studies and some other fields which would normally be taken as part of a BA.

Also, Warren looks only at domestic students (which is, after all, what the government and the local labour market have a primary interest in). But from the point of view of academic departments in a university, what matters from a resourcing perspective is the total level of enrolment – how many equivalent full-time students (EFTS) in total, irrespective of their origin or where their resourcing comes from.

So, in the analysis below, I have looked at total enrolments and graduations – including domestic and international students, I have used more recent data and I have reconstructed the data[4] to create a humanities grouping and a social sciences grouping – see Appendix 1 for the lists.

Looking at the data more closely…

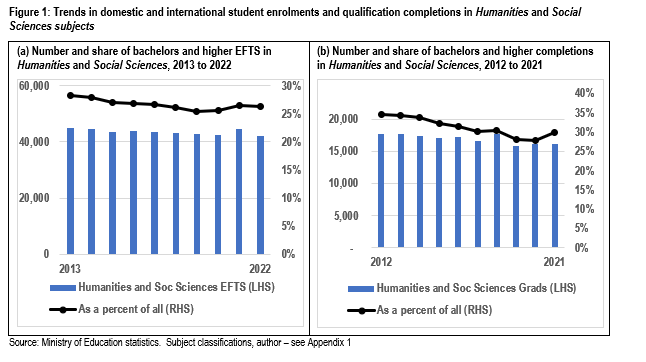

In the graphs below, I look at total EFTS (domestic plus international) over the 10 years from 2013 to 2022 and the qualification completions in the decade 2012 to 2021 at bachelors level and higher, comparing humanities and social sciences to the system total.

The Humanities and Social Sciences share of total EFTS fell from 28% to 26% over the decade. There was a similar pattern with the number of graduates. With 26% of all EFTS in 2022 and 30% of all graduates in 2021, Humanities and Social Sciences – the BA in fact – remains the largest area of study at degree level across the system. Yes, the share has fallen. But it is wrong to imply that the traditional BA is in desperate straits. The question on the cover of The Listener has to be answered in the negative.

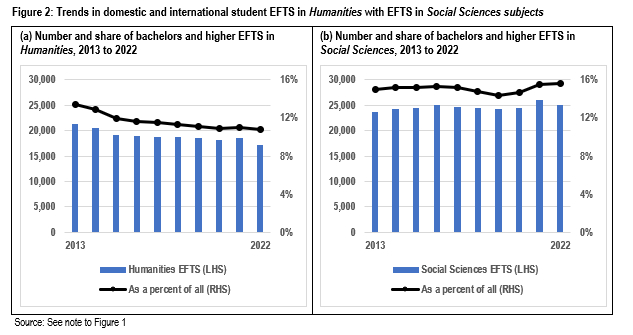

It is useful to separate the humanities from the social sciences because these two subgroups show quite different trends. At the beginning of the period, Humanities subjects were 44% of the Humanities and Social Sciences total. By the end of the period that had fallen to 36%. It’s the same in enrolments; the Humanities share fell from 47% in 2013 to 41% in 2022. That suggests that the fall seen in Figure 1 is especially influenced by the Humanities trend, rather than Social Sciences.

Figure 2 compares the EFTS count and share in Humanities with that in Social Sciences.

The same trend is replicated in the graduate numbers; the Social Sciences share is broadly stable over the ten-year period, while Humanities has fallen (from a 15% share to 11%).

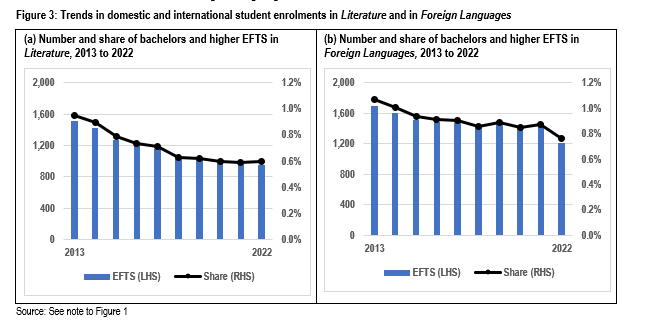

Within the Humanities group, the detailed NZSCED field of Literature – the subject of much of the discussion in Paul Little’s article – has experienced especially pronounced falls. We see the same trend in the detailed field of Foreign Languages.

Figure 3 speaks for itself. Literature EFTS fell by 37% over the period while Literature graduate numbers fell by 45%. For Foreign Languages, the falls were 28% in EFTS and 30% in graduate numbers.

So while there is no strong evidence that the BA as a whole is dying, the fields of Literature and Foreign Languages – once the choice of many, many students – are on life support. The rise of Asian languages in our universities hasn’t offset the fall in European and classical languages.

That does confirm the anxiety of the English academics who spoke to Paul Little for his article.

Going back into the distant past …

Paul’s informants, however, may have been pining for a more distant period than the last ten years – looking back to a time before the 1989 Learning for Life reforms[5]. And it is true that the arts degrees had a greater share of the total then.

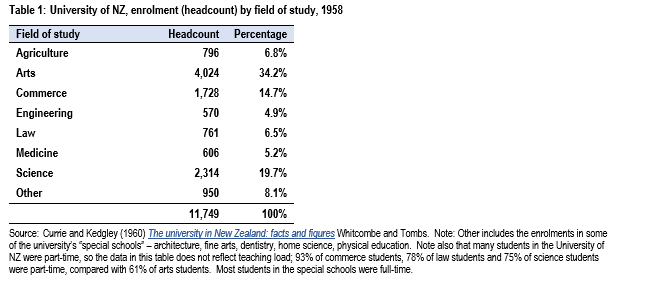

Enrolment data from the University of New Zealand in 1958 shows that arts attracted the largest group of students:

With more than a third of all students (and approximately 32% of EFTS), arts was by far the largest of the groupings[6]. Arts also accounted for 42% of graduates in 1958.

When the University of NZ was disestablished in 1961 and its assets distributed among its constituent colleges, Victoria University College didn’t inherit any of the university’s “Special Schools” – architecture, medicine, engineering, fine arts, dentistry etc[7]. That meant that, of the four newly autonomous universities that opened their doors in 1962, Victoria was the one with the largest concentration of arts subjects. In fact, in the 1960s and 1970s, Victoria had two arts faculties – one for languages and literature and one for other arts subjects. Like most NZ universities, Victoria required graduates in many fields to have at least a reading knowledge in a foreign language – which provided a subsidy to the language departments. In the year May 1973 to April 1974, 45% of the degrees conferred by Victoria were arts degrees, with science 26%, commerce 18% and law 7%. Arts degrees were by far the largest group.

Even now, arts remains the largest group in the NZ university system, but its share of the total number of graduates has dropped by a little more than 10 percentage points in the six decades since the disestablishment of the University of New Zealand.

Why the fall?

One key factor that drives institutions’ internal resource allocation is student load. If a discipline begins to lose enrolments, it is at risk of losing resourcing. Loss of resources may constrain the range or quality of what the departments responsible for that discipline can offer, possibly resulting in even greater loss of students.

We saw above that the proportion of students selecting Social Sciences[8] as a field of study has been more or less stable but that some humanities fields have experienced severe losses of student load over the last decade. Languages and Literature, but also, if to a lesser extent, History and Philosophy.

Why is that?

What do we know about students’ choices of field of study?

The choices learners make about higher education – including field of study, type of programme and education institution – are decisions taken under uncertainty. The decision to enrol in higher education presents a trade-off between immediate costs and future benefits. When confronted with intertemporal decisions, decision-makers tend to base their decisions on underlying beliefs about future events, and to assume that their future preferences will be similar to their current preferences[9]. In a discussion of models of education and career decision-making, Hofer, Zhivkovikj and Smyth (2020) draw from the behavioural economics literature to analyse young peoples’ biases, their use of heuristics when confronted by options, and their reliance on the example of peers, parents and other influencers.

Synthesising the findings of more than 50 studies of student post-secondary education decision-making from NZ, Australia, the US and the UK, Massey University researchers Linda Leach and Nick Zepke (2005) identify socio-economic factors, family experiences and parental advice, academic aptitude and subject area interest as the important factors leading to decisions. They note that subject area interest also “stands surrogate for career aspirations”.

A series of papers by University of Melbourne researchers[10] suggests that interest in a field of study combined with the desire to create job prospects are important motivators of choice of the area of specialisation. Interest is also cited as a principal driver of subject choice in numerous other studies – see for instance, Vulperhorst et al (2020) – while having experience of and familiarity with (and therefore, confidence in) a field is also a factor (Vulperhorst et al (2020), Denice (2020) and Fricke (2018)).

Data from the four-yearly Australian Bureau of Statistics work-related training survey shows that between 70% and 80% of respondents to the survey over 2005 to 2017 reported job/career-related reasons as the primary influence of their choice of study, with interest/enjoyment reasons at between 10% and 20%. Analysing the data, Andrew Norton (2020), notes that these two reasons are not mutually exclusive. In surveys where respondents are not forced to select a single reason, interest in the field of study is selected as an important influencing factor by 90%+ of respondents, with job-related reasons at around 85%. Norton (2016) argues that “… student course choices are structured by their interests and aptitudes, [but] precisely which courses they choose is influenced by what they hear and observe. We can see publicised ups and downs of the labour market flowing through into applications and enrolments ups and downs”.

Drawing together those findings, we can conclude that young people want to strengthen their employment prospects through study, but that they want to study what they are interested in. On the whole, students choose a specialisation that interests them and that also helps their career prospects. The two are intertwined. Interest is an important factor in driving success; studying a field with great employment prospects but where the student has low interest does not lead to success[11].

Can the political culture affect subject choice?

Paul Little’s Listener informants imply that they see the dominant political culture and successive governments’ focus over the last 35 years on scientific and technical skills as having contributed to the move away from humanities enrolments.

Norton (2016) argues that government campaigns can make a difference at the margin to students’ choice of specialisation. He notes that enrolments in STEM fields in Australia increased in response to evangelism for science, led by political parties and by the national science establishment (leading to an oversupply of graduates in science).

The NZ government’s E2E (education to engineering) initiative was intended to address our very low number of engineering graduates. E2E attempted to remove blockages in pathways, foster better engagement between the profession and institutions and improve information. Bachelors level enrolments in engineering rose by around a quarter between 2014 and 2017 before stabilising at that higher level[12].

Also, parents’ advice might reflect their assessment of what sectors of the economy will flourish and that view may reflect what they have heard from the government. Just as, in the zaniest careers advice session in Hollywood history, Mr McGuire (in the 1967 movie The Graduate), reflects a then dominant view when he assures Benjamin that the future lies in plastics. So some young people may take on the government’s view of the future of the labour market through the medium of advice from influencers …. But that’s indirect. It might coincide with (but would be unlikely to trump) an intending student’s interests.

The message for advocates of humanities disciplines – you have to position your field as interesting! It was unwise for instance, for English literature majors to have to read the entire canon in chronological order, as occurred as recently as the 1970s in some NZ universities, so that it took until late in year three to reach the twentieth century[13]! English departments seemed oblivious to the fact that students can gain the key generic skills and they can develop a sensitive appreciation without reading the entire the canon in precise date order.

What we know about the employment prospects of arts graduates

If choice of specialisation depends primarily on students’ interests tempered by perceptions of employability, what can we say about the employment prospects of the traditional arts subjects? Employability refers to a graduate’s achievements; it is a measure of the potential to lead to a ‘graduate job’[14]

In the Listener article, Brigitte Bӧnisch-Brednich, an anthropology academic, states that all her graduates do get jobs; she lists the sorts of jobs anthropology graduates end up in and she (and some of the other informants for the Listener article) gives an account of the kinds of generic skills an arts degree provides, skills like critical thinking.

The British Academy, in its recent report on the state of English studies in UK higher education noted that graduates in social sciences, humanities and the arts “will have developed eight of the top 10 skills declared as essential for 2025 by the World Economic Forum” – these include analytical thinking and innovation, critical thinking and analysis, complex problem solving, reasoning, problem solving and ideation …[15] Those are certainly skills that (in theory at least) are independent of the disciplinary context within which they are imparted..

However, the transferability of skills – the idea that skills acquired in one context can readily be applied in another – cannot simply be taken for granted. Mantz Yorke (2006) warns of the risk of simplistic thinking about the transferability of generic skills; drawing on the work of David Bridges (1993), Yorke argues that a person needs to be able to “select, adapt, adjust and apply” these generic skills to different contexts. Transferability is not simply a question of the nature of the skill; it is also about the capability of the person to transfer that skill.

So while many of the skills taught in arts subjects are unquestionably generic, they become transferable skills only if the student has been helped to acquire the capability to apply those skills in different contexts. That depends on the capability of the student but also the skills of the teacher.

The key take out:

Most humanities and social sciences subjects build generic skills that offer the potential for transferability… But studying a subject that inculcates generic skills doesn’t guarantee that those skills will be transferable. To realise the potential requires the student to develop the capability to use those skills in multiple contexts.

What are the actual employment outcomes for arts graduates?

So what does the data tell us about the employability of graduates in humanities and social sciences in NZ?

Research has identified level of study as the first determinant of employment outcomes and field of study as the second determinant. So that, overall, masters degrees have better outcomes than bachelors degrees which have better outcomes than diplomas and so on[16].

An important first observation from the data is that unemployment rates are negligible among young bachelors graduates five years out from study. In fact the number of unemployed bachelors graduates in nearly all fields is so low that the data has to be suppressed for confidentiality reasons. That applies to traditional BA fields, as well as to more vocationally oriented fields such as IT and accounting[17].

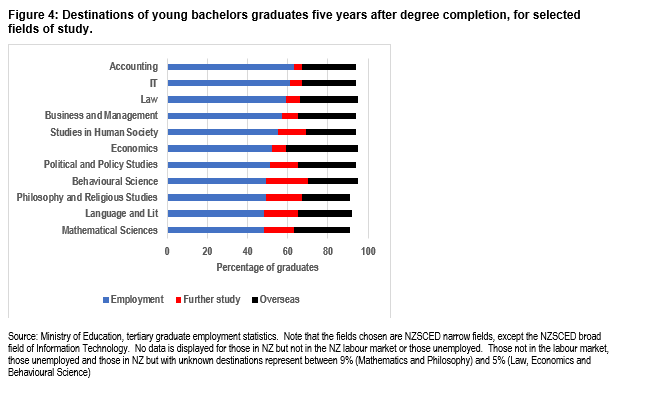

Figure 4 looks at young bachelors graduates five years after graduation and reports on their principal destination – are they in employment, in further study or overseas? We report this for graduates who have majored in a group of fields – six arts degree majors plus some others as comparators.

While there is all but zero unemployment by field of study, there are differences in destinations. Graduates in vocationally-oriented fields – accounting, IT and law – are more likely to be in work. Economics graduates are most likely to be living overseas. Graduates in many of humanities/social sciences fields have the highest rates of return to study.

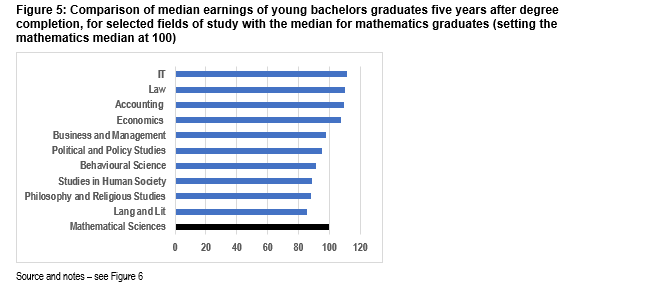

Focusing only on those whose principal destination is employment, there are also differences between these fields in the earnings of graduates. Figure 5 below looks at the relative earnings five years after completion of bachelors graduates who are in employment, with same selected fields of study as Figure 4.

The field with the lowest earnings profile of those shown in Figure 5 is Language and Literature. The five fields with the lowest median earnings are all traditional BA majors. The two humanities fields (Language and Literature and Philosophy and Religious Studies) have the lowest medians. The only social science in Figure 5 with relatively high earnings is Economics, whose median is fourth highest (but whose upper quartile earnings is the highest of all the subjects.in the selected fields).

The findings above are not news to anybody; humanities subjects have long been known to lead to lower earnings in the early years post-graduation. Has knowledge of the lower earnings potential of humanities fields made a difference to students’ choice of field? We can’t say for sure.

What about research in the humanities and social sciences?

In the present financial crisis across the system, much of the talk is about student numbers and teaching. Inevitably. It is a university’s teaching that drives profitability, with financial surplus highly correlated to the ratio of students to staff. Research rarely contributes to the bottom line; research contract revenue in a university is largely (usually entirely) spent on the contracted research with a contribution to institutional overheads, but no actual surplus. But, according to the legislation[18], teaching and research are interdependent and most degree level teaching is to be done by those active in research. This means that the credibility and standing of our universities’ arts degrees is linked to the research capability of the departments responsible for teaching those degrees.

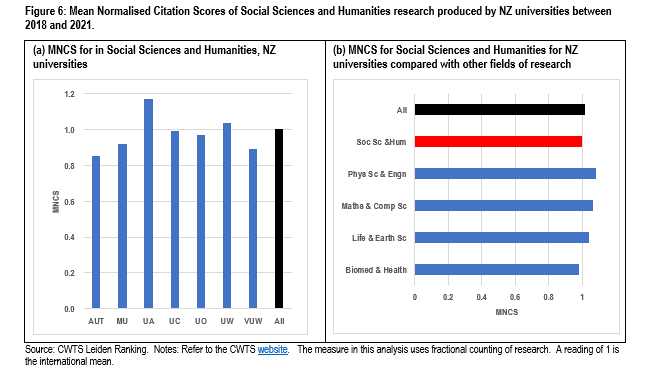

So it’s worth looking at how our universities’ research in humanities and social sciences measures up. Data from the University of Leiden’s CWTS programme allows us to get a sense of how well researchers in these fields compare with those in universities in other countries. In the figures below, I show at the Mean Normalised Citation Score (MNCS) for the universities’ research in Social Sciences and Humanities. The MNCS counts how often papers are cited compared with the average for all other research papers in the Web of Science database in same field[19] over the same period. A score of 1.0 means that the research is exactly on the world average. A MNCS score less than 1 means that the research is cited less than average, so its impact on other researchers in the field is less. It’s a relatively crude measure but it gives a quick and simple snapshot view of the international standing of the research.

.Social Sciences and Humanities research produced by NZ universities has a MNCS of 1.00, in line with the international mean. This is bolstered by higher than average MNCS readings for the Universities of Auckland and Waikato which, together, are responsible for around 35% of the total. The reading of NZ’s Social Sciences and Humanities research is fractionally less than the national total (1.02).

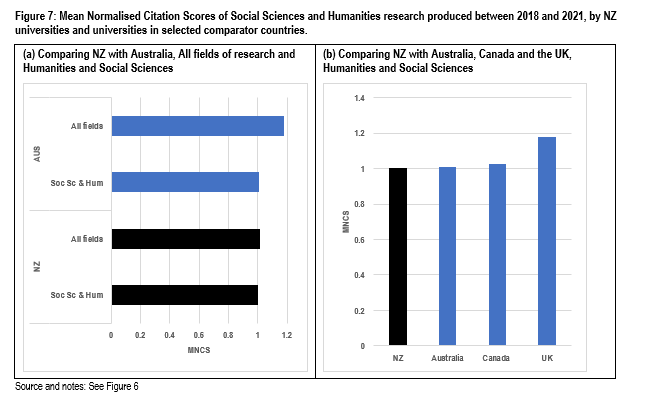

Figure 7 compares NZ with other countries.

Despite the fact that research performance over all fields is stronger in Australia than in NZ, there is almost no difference between the two countries in the MNCS in Humanities and Social Science (with Australia at 1.01). Likewise, Canadian universities’ Humanities and Social Science MNCS (1.02) is only fractionally above that of Australia and NZ.

Figures 6 and 7 show that, overall, the NZ university system’s research in these fields has reasonable international standing[20]. One consequence is that any staffing reduction in these fields as universities deal with the financial crisis needs to be carefully targeted to ensure that research capability and research critical mass are maintained. The credibility of the degrees rests on that.

The place of the humanities in the current system financial crisis

In a time like the present, where most of the universities have faced deficits, where financial prospects look bleak, where future deficits are likely (notwithstanding the recent increase in funding rates for 2024/25) institutional leaders will need to continue to look at where they can reduce expenditure, while causing least reduction in revenue.

Fields that have struggled to draw in students or where enrolments are falling are among the first to be subject to scrutiny. Victoria University | Te Herenga Waka has been consulting on discontinuing German, Italian, Latin and Greek among other fields, while Theatre, Linguistics and Museum Studies have been proposed for restructuring – integrated into broader programmes in order to reduce outgoings. All traditional BA fields.

Likewise, arts subjects were among those targeted for reductions in the AUT consultations with staff in late 2022 – including several majors in the BA (such as English, new media, Japanese and Chinese).

The likely consequence will be a reduction of capability in humanities and social sciences across the system.

A major challenge for the universities is to work out how they might coordinate the focus of their cuts so as to consolidate capability – so that universities, acting independently, don’t target the same fields for cutting; for example, it would be better for the system if at least one, possibly two institutions teaching classics retained capability in the field.

That is the critical priority for the system now – if the system as a whole is to maintain its breadth overall and its credibility in traditional arts fields, there needs to be collaboration and some level of consolidation to maintain and build on the existing strengths, both in teaching and in research.

Of course, it’s great that the government has recognised the urgency of the situation faced by the system. But the level of additional funding isn’t nearly enough to save all the fields and all the programmes that are currently facing the risk of cutbacks – and the humanities are at the head of that queue.

To summarise …

No, Paul Little, the BA is not on death row. Not yet.

Degrees in traditional BA subjects (whether called BA or BSocSc or Bachelor of Communication or Bachelor of Global Studies or some other engaging name) still represent the largest group of graduates from NZ universities. Yes, arts degree numbers are inching downwards but at a slow rate. If the decline were to continue at the current rate, it would be many decades before its condition could be described as terminal.

But there is a shift within the BA away from the humanities and towards the social sciences. The decline in the humanities is acute.

Of course, graduates in the humanities will get graduate-level jobs, so some level of employability is obviously an outcome of the degree. But the earnings data presented above raises a question about how well the labour market values the skills of humanities graduates.

It’s not enough simply to insist that humanities graduates have transferable skills. It’s also important for academics to ensure that their students pick up the capability to enable them to ensure that the generic skills the students learn can be, and are, applied in whatever context the graduate works in. That is a meta-cognitive skill that all graduates, not just BA holders, need if they are to succeed in a changing labour market.

This is especially important now as we enter a period of restructuring and retrenchment, when university leaders have, in some cases, signalled that some majors, some whole subject areas may be unaffordable, may have to be cut altogether. The challenge is to find how the system can retain national capability in valuable fields of study, even as some institutions close programmes and departments in the effort to retain viability and quality.

References

Bridges D (1993). Transferable skills: A philosophical perspective Studies in Higher Education 18. 43-51

Currie G and Kedgley E (1960) The university in New Zealand: facts and figures Whitcombe and Tombs

Denice P (2020) Choosing and changing course: postsecondary students and the process of selecting a major field of study Sociological Perspectives 64(1) 82-108

Fricke H, Grogger J and Steinmayr A (2018) Exposure to academic fields and college major choice Economics of Education Review 64 199-213

Hofer A-R, Zhivkovikj A and Smyth R (2020) The role of labour market information in guiding educational and occupational choices OECD Education Working Paper No 229, OECD

James R, Baldwin G and McInnis C (1999). Which university? The factors influencing the choices of prospective undergraduates. Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

James, R. (2000). How school-leavers choose a preferred university course and possible effects on the quality of the school-university transition. Journal of Institutional Research, 9 (1), 78-88.

Leach L and Zepke N (2005) Student decision-making by prospective tertiary studentsMinistry of Education

Mahoney P, Park Z and Smyth R (2013) Moving on up, Ministry of Education

McInnis, C., James, R. & Hartley, R. (2000). Trends in the first year experience in Australia Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs.

Norton A (2021) : The first Job-ready Graduates university applications data Higher Education Commentary from Carlton

Norton A (2020) Jobs, interests and student course choices Higher Education Commentary from Carlton

Norton A (2016) 18 year olds or politicians: who makes better course choicesHigher Education Commentary from Carlton

Roberts G (2021) The humanities in modern Britain – Challenges and opportunities Higher Education Policy Institute

Rounds J and Su R (2014) The nature and power of interests Current Directions in Psychological Science

Royal Historical Society (2023) History in UK higher educationRoyal Historical Society

Smart W (2018a) What are they doing? Ministry of Education

Smart W (2018b) What did they do? Ministry of Education

Smyth R (2012) Two decades in the life of a small tertiary education system OECD

Thain M et al (2023) The humanities in the UK: What’s going on Higher Education Policy Institute

The British Academy (2023) English studies provision in UK higher education

Usher A (2022) The state of postsecondary education in Canada 2022 Higher Education Strategy Associates

Vulperhorst J, van der Rijst R and Akkerman S (2020) Dynamics in higher education choice: weighing one’s multiple interests in light of available programmesHigher Education 79: 1001-1021

Yorke M (2006) Employability in higher education: what it is, what it is not, The Higher Education Academy

Yorke M and Knight P (2004) Embedding employability in the curriculum Learning and Teaching Support Network

Other Sources of Information and Data

Australian Department of Education and Skills

NZ Ministry of Education

CWTS University of Leiden

UK Research and Innovation

World Economic Forum

[1] A number of Little’s interviewees used some data. But nearly all of the data quoted is unrelated to the topic under discussion. The same applies to Little’s informants’ analysis.

[2] Smart’s analysis used the NZSCED classification system – that has 12 broad fields of study that split into 71 narrow fields and several hundred detailed fields. of graduates’ specialisation looked at the major field for the qualification. Thus, a person who majored in economics for a BCom and an economics major who graduated BA are both allocated to Society and Culture. Note also that, if a student majored in two fields – say economics and business management, then that completion is counted both in Society and Culture (for the economics) and in Management and Commerce (for the management major).

[3] NZSCED stands for the “NZ Standard Classification of Education”. It is derived from UNESCOs subject classification system (part of the ISCED system) and harmonised with the corresponding Australian system.

[4] In reaggregating detailed fields to form the Humanities and Social Sciences total, some enrolments/completions are double counted. This is because each student is counted in each of his/her fields of specialisation. However, as we are primarily interested in the trend over time, the data in Figure 1 is a fair proxy.

[5] Refer to this historical account of the system reforms and the rationale for them.

[6] The estimated EFTS load was calculated by assuming each part-timer had a .25 EFTS load.

[7] See Currie and Kedgley, op cit. There was a very small number of students (25 in 1958) in a special school in social science and public administration at Victoria.

[8] Noting, however that some social sciences (especially policy studies and psychology) rose but others (economics, sociology, anthropology) have declined.

[9] See Hofer, Zhivkovikj and Smyth (2020) The role of labour market information in guiding educational and occupational choices OECD Education Working Paper No 229, OECD

[10] These papers were produced by researchers from the University of Melbourne’s Centre for the Study of Higher Education (CSHE). The lead researchers were Professors Richard James and Craig McInnis. See the list of references for the titles of the papers.

[11] Refer to Rounds J and Su R (2014) The nature and power of interests Current Directions in Psychological Science. They find that interests is crucial to success in study and in careers – second only to ability and more important than personality.

[12] It’s not possible to establish how much of the engineering rise was actually due to E2E. However, over the period when engineering enrolments rose, total enrolments in the same qualification levels across all fields of study fell by 2%.

[13] Refer to the British Academy (2023). The “entire canon in date order” approach was obviously pioneered in the UK!

[14] Noting, however, that this differs from the actual acquisition of a ‘graduate job’, which depends, not only on the skills and attributes the graduate brings but also to the context and in particular, the demand for and supply of labour in the economy. See Yorke (2006).

[15] Refer to https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020/in-full/infographics-e4e69e4de7/. The two listed essential skills not covered in the traditional BA subjects are: technology use, monitoring and control; and technology design and programming.

[16] Refer for instance to Mahoney P, Park Z and Smyth R (2013) Moving on up, Ministry of Education

[17] Refer to the data on tertiary graduate employment and tertiary graduate earnings on this page

[18] See Education and Training Act 2020 s268(2)(d)

[19] The Leiden analysis maps more than 4,000 research subfields to the 250+ fields used in the Web of Science and then groups the results into five broad fields, of which one is Humanities and Social Sciences

[20] The interpretation of the MNCS in Humanities and Social Science needs to acknowledge that much research is culturally linked to its region of origin, which may have a depressing effect on the score in NZ – a small country far from the larger countries in the global north. In that context, a national MNCS of 1.00 is a good result.