Everyone knows now that the universities are facing serious financial challenges – leading the government to provide extra funding for degree-level tertiary education for the next two years. In their funding announcement the Ministers of Finance and Education told us that the injection was temporary, buying space for a complete review of the funding system.

What’s in a review? This article summarises the problem and then looks at that question.

Why do we need a review?

Student numbers are at the heart of the problem …

Tertiary education organisations’ finances depend on scale. In most circumstances, the marginal cost of an additional student on the roll is low in relation to the revenue that student brings. So student numbers really matter to the financial health of a provider.

In 2022, the universities saw a drop in domestic enrolments of nearly 4%. The Ministry of Education’s forecast outturn for 2023 is for a fall of a further 5.3% and only small annual increases from now through to 2027. Those forecasts have a history of being very, very accurate[1]. That means that there is unlikely to be any respite for the universities from the domestic market for several years.

Even with the borders open, international student numbers are likely to recover only very slowly; existing students are completing and leaving, the Chinese market has been slow to get going and other countries (especially Canada, Australia and England) have been faster to open their gates to international students. And even when intakes return to pre-Covid levels, it will take three years or so for the cohorts to move through and numbers to reach stability.

… leading to constrained revenue and financial vulnerability …

The weak international enrolment is a real problem. International fee income is the one revenue line that universities can control. Each international student generates about 1.6 times the revenue of a domestic student. Therefore the proportion of internationals in a university’s student body is an important driver of an institution’s productivity and financial health.

Budget 2022 saw funding rates rise by 5% – an increase less than inflation. Meanwhile, domestic student fee increases were limited to 1.7% for 2022 and 2.75% for 2023 – meaning a rise of only 4.5% for the two-year period – a period that saw the CPI rise by 14%![2]

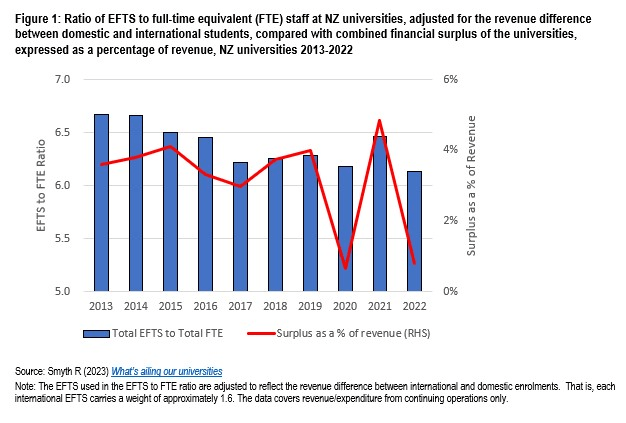

One predictor of institutional efficiency is the ratio of students to staff – total EFTS, domestic and international, to total FTE staff, academic and professional. On this measure, 2022 gives the lowest reading in 20 years.

Statistical analysis shows that the adjusted EFTS to FTE ratio is highly correlated to profitability[3].

So, unsurprisingly, a majority of universities were in deficit in 2022 and the outlook for 2023 looks negative. Victoria for instance, expects the year end deficit to be above $30 million. AUT is forecasting breakeven, missing its budget target by more than $6 million.

… and cost cutting …

And those projections are driving the cost cutting and job cuts at Otago, Massey, Victoria and AUT. Some programmes are at risk. Even more concerning is the risk of loss of capability in the system; when academics are laid off, they take with them their research capability.

It’s no surprise that some universities have looked hard at their finances, developed their forecasts and decided that there is no way of avoiding painful cuts. The alternative is the loss of the capacity to invest in the quality of their institutions. However painful and despite the risks to institutional capability and credibility, the universities that have proposed cuts are acting prudently.

… and an inevitable reaction from the government …

The storm of protest raised by the planned cuts forced the government’s hand. The Ministers of Finance and Education announced a further increase to the funding rates for enrolments at degree and higher, $64 million a year for each of the next two years, again, funded out of underspends in the tertiary education appropriation. The government’s purpose is to tide the system over while there is a review of the whole funding system. “Including the PBRF!”, the minister said. Including the PBRF? That’s a matter we will return to!

Is it enough? A help, certainly, but not enough to solve the immediate crisis completely. The University of Otago faces a $60 million hole and is expected to gain around $10 million in each of 2024 and 2025, while Victoria is forecasting a $30 million deficit and is set to gain around $6 million a year. Enough, however, to allow the proposals to be reviewed and, possibly, trimmed.

A history of reviews …

Much of the architecture of our funding system derives from Learning for Life – the government’s decisions on the Hawke report of 1988[4]. Settings have been modified, frequently, annually, almost continuously, but many of the principles proposed by Hawke and adopted by the government have endured to the present.

Since then, there have been two comprehensive reviews …

- The Ministerial Consultative Group (MCG) of 1994 which led to a series of funding rate reductions saw students pick up a greater share of the cost, with the loan scheme to maintain affordability and access.

- The Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (TEAC) – whose brief was wider than funding but much of whose work centred on funding. Their work led the government to unbundle research funding from tuition funding (leading to the creation of the PBRF and the Centres of Research Excellence), to indexation of funding levels (introduced late in the term of the Clark government but abandoned in 2009 in the wake of the GFC).

The government’s decisions on the TEAC’s four reports have underpinned much of the system architecture since – not in every detail, but in principle[5].

As well, there have been dozens of tweaks and adjustments, especially during the 1990s when the funding system was adjusted pretty much each year – not just the funding levels, but also minor changes to the structure of the system, although without changing the fundamental architecture of the system.

The lessons for this new review

OK, let’s pretend it’s not election year. Or if that’s too much of a stretch, let’s imagine instead that this new review will take place whichever party leads the next government, whoever is minister at the end of this year.

And let’s take the ministers at their word. Reading their release, they imply that they believe the problems faced now are not really about the quantum of funding or the level of the funding rates. Meaning that they suspect that the problems derive from incentives built into the funding system, incentives that make it less likely that institutions will act prudently. So that the challenge we face now is systemic, a problem that was masked for years by the stream of ready cash from international students but laid bare when that revenue stream turned down.

What does the history of reviews tell us?

Structuring a review

Comprehensive reviews of major policy areas can be of two sorts:

- A review by experts and stakeholders from outside the government agencies – like TEAC, like the MCG, like the Hawke review – supported by policy, analytical and research staff from the agencies (like the MCG) or by a secretariat appointed from outside the agencies (like TEAC)

- A review by officials from the agencies, supported by a consultative group of experts from sector experts and/or stakeholders – such as the 2012/13 PBRF review, the 2012/13 review of the industry training system and the set of reviews of tertiary education in the late 1990s, that led to the series of green and white papers[6].

The current government has tended to use the first option – think the Welfare Working Group, the Tax Working Group and, in tertiary education, the 2019 PBRF review led by Linda Tuhiwai Smith. The Review of Vocational Education (RoVE), however, was led by officials.

The previous government tended to opt for the second form – for example, the 2012/13 reviews of the PBRF and industry training, both of which were run by officials, working to the minister.

The first sort of review – an independent review panel – will have greater credibility with the public and stakeholders, can generate richer engagement from the sector and can bring greater breadth of ideas and proposals. But … it necessarily involves a second stage in which the government makes decisions on the proposals from the independent group (like the move from the Hawke report to Learning for Life). And that can lead to disappointment when (possibly unrealistic) expectations are dashed. Again, think of the Tax Working Group and the Welfare Working Group.

One of the TEAC commissioners, Jonathan Boston, expressed disappointment[7] at the way the government treated some TEAC proposals – for instance, the decision to make the TEC a Crown agent (rather than an independent crown entity[8]) and to deny TEC a policy role. He also argued that one of the most serious constraints on the review was that its advice was to be formulated “within the context of the overall level of funding” and that TEAC was “to avoid discussion of the overall quantum of funding”. In other words, as an expert advisory body independent of government agencies, TEAC was free to propose new ways of allocating funding, but funding levels are, and will always be, must always be, a matter for ministers, advised by policy agencies.

On the other hand, an officials-led process would be iterative, with frequent check-ins with the minister, so that strategic decisions will always mirror the minister’s preferences. The mass of papers released on the RoVE review shows what I mean. But it’s wrong to think that a review led by officials will necessarily be more modest than an independent working group – RoVE was anything but modest.

The first question that the minister needs to decide is scope – what elements are in and what are not. That will define the review structure. If the focus is primarily on the quantum of funding, the review will likely be an officials review, working under the minister’s direction. But as I noted above, my take is that ministers have seen the problem as systemic, with funding rates a subordinate question[9]. If my guess is right, the current government is more likely to see the best way forward as a review led by a sector/stakeholder group.

What are the questions to ask in the review …

The review is confined to degree-level and postgraduate education, wherever delivered, not just universities but also wānanga, Te Pūkenga and private training establishments. In other words (with vocational education now operating under its own brand new unified funding system), this review is confined to what would be called in other countries the funding of higher education.

So again, let’s just use our imaginations … let’s imagine that the scope is broad and then, let’s look at the questions that the reviewers need to address.

What outcomes do we want from a higher education funding system?

A higher education system exists to build human capital and social capital, to create the capacity for innovation, to enhance and develop the culture of a society and to critique, disseminate and preserve the culture. To provide individuals with skills – social, emotional and cognitive – and knowledge that enables them to function in a modern society, in its economic, social and cultural life. To provide the NZ society, including (but not only) the labour market, with the human and social capital, the capacity for innovation and the diversity of skills and knowledge that we all need for our society to prosper. That is the value that higher education contributes.

As society becomes more complex, as it addresses the challenges we face, as the need grows for ever more skills and for more sophisticated skills, we need to expect our higher education to be accessible and equitable. It needs to enable diversity of participants.

Those are the enduring goals of a higher education system.

Funding sets incentives. Institutions – and the individuals that manage them – respond to those incentives. So funding can either advance those outcomes or else skew the system and distort what the system produces. If we want the system to deliver value, we need a funding system that helps serve that end, helps deliver on those outcomes. The funding system needs to serve, in other words, the enduring role of higher education. The design of any funding system needs to be cognisant of the risk of perverse outcomes.

And we need a funding system that ensures the sustainability of the system. Sustainability means that institutions have the ability to generate financial surpluses at a level that enables them to improve and invest in their assets, to improve their systems, services and facilities – to enhance their quality. Breakeven leads to erosion of quality.

But sustainability means that institutions shouldn’t be able to make excessive surpluses – if institutions can readily generate very high surpluses, then that means that funders (government and students) are paying more than they should. Resourcing needs to be at a level that obliges institutional managers to manage well and prudently, but that allows the sort of surpluses that are needed for maintenance and enhancement of assets.

In an article in The Conversation, University of Auckland scientist, Professor Nicola Gaston, argues that the review needs to ensure that the review enhances equity and value (to society in particular) and diversity. I would go along with that.

When this review is complete, we need to score the discussion, the proposals and the recommendations by how well they align with the ongoing outcomes of a tertiary education system, and with the fundamental purpose of a funding system, and on how the review deals with the architectural principles I discuss below.

The architecture of a funding system

One of the things that any comprehensive review of the funding system needs to address is the architecture of the system components, how they fit together. There are many international models that help – in particular, the countries in the European Higher Education Area publish comparative overviews[10]. And current debates in Australia and the UK[11] over the shape of their HE systems contain rich information about the pitfalls that await the unwary.

Architectural principles

Focus on enduring system goals

The first design principle is that the architecture must ensure that the funding system – which creates the most powerful incentives – is fit for the purpose of delivering those enduring system goals.

It’s tempting to use funding to incentivise strategic priorities. But experience suggests that can be problematic. The Australian Job Ready Graduates initiative, which sought to use the funding system to direct more enrolments into areas considered by the government to be more job rich was ill-conceived[12]. And the TEAC aspiration for a strategic relevance dimension in funding was never able to be developed in a satisfactory way and was eventually quietly dropped.

Funding needs to mesh well with other system levers

The second design principle to be addressed is to ensure that the funding system works with, reinforces, is reinforced by the other levers government has:

- the system planning and steering approach

- the regulation of tuition fee setting – what share of the cake should be paid by students, who sets the fees and what controls should apply

- the student loan scheme which gives almost universal access to finance for fees, guaranteeing the affordability of higher education fees for most

- the student living costs support system – through the loans and allowances[13] schemes

- and, in particular, the quality assurance system, which ensures that what is delivered is fit for purpose and which incentivises continual performance improvement in providers.

Simplicity vs complexity

One of the key trade-offs to be made is between simplicity and complexity. Too simple and we risk missing the mark. An example is the EFTS funding system we had in the 1990s, a system as simple as one could conceive, when there was only a single driver of funding, meaning that base research funding was driven by student enrolments – despite the fact that the drivers of cost, and capability needs and the planning horizon are so different between tuition and research; of course, research and teaching are interdependent in HE, but aligning the funding drivers in that way was problematic; it penalised research intensive institutions and rewarded those that were research-light.

On the other hand, too much complexity, too many components, too many funding streams creates incentives for institutions to focus their energy and time on winning, rather than using, funding. Multiple funding streams can encourage institutions to select targets to chase, trading off high performance in one area against weaker performance in another, risking unbalancing the system[14].

Sharing the cost

The architecture of the funding system needs to recognise that the benefits of higher education are shared between the society at large and the individual[15].

- Graduates earn higher incomes and hence, pay higher taxes, contributing to the social and public good. Tertiary education also generates the technical skills that societies need, for instance the skills used in the health, education, legal and financial systems so it lowers the price that the society pays for those services. And tertiary education is also associated with social benefits like greater civic engagement and better health.

- There are also private benefits in the form of higher earnings. There are also non-market private benefits (like greater life satisfaction and better health). There is a private benefit from higher levels of education in all types of economies.

As a result, government’s higher education spending is regressive. That justifies a student contribution to costs. Any comprehensive review of funding must at least touch on this question.

Competition vs collaboration

The fourth principle relates to how the system operates as a system – the vexed question of competition vs collaboration. Again, here, it’s a matter of finding a right balance. Those of us who have been around the system for a long time remember that the absence of competitive edge in the system in the 1970s and 1980s was corrosive, leading to complacency in institutions, poor service to students, homogeneity of institutions and a lack of incentives to improve. Nicola Gaston, in her article also celebrated the fact that “each university has its own identity”, a consequence of the competitive edge.

On the other hand, excessive competition carries risk – as we have seen with the risk of the loss of national capability in a discipline if several institutions, acting autonomously, all decide to cut in the same fields. That means that the design needs to enable institutions to work in collaboration, while also maintaining a competitive edge.

Capital

The fifth principle relates to financing of capital expenditure. Currently, institutions are responsible for providing financing for their own capital development, through use of accumulated reserves, endowments or borrowing. Having the power to control capital spending – to choose where to invest, how much to invest and the timing of investments – is a prerequisite for institutional operational autonomy. And that requires that the funding system enables well-managed institutions to operate sustainably (ie, funding must be sufficient to generate reasonable surpluses). Capital funds managed by governments compromise autonomy and is likely to lead to perverse prioritisation.

Higher education’s role in the community

While the funding system needs to focus primarily on the two main outputs of higher education – producing graduates (ie tuition) and producing research – institutions are repositories of knowledge and expertise, and they contribute that expertise to the community through technology transfer, advice and comment. That role springs from the teaching and research expertise brought together by the institution to service its two primary roles. While it needn’t be part of a funding formula, the government needs to allow space in the funding for that sort of activity.

Detailed design elements

Teaching vs research

The two primary output areas in higher education – tuition and research – are interdependent. Two different activities that draw on the same group of individuals – scholars, individuals whose scholarship enables most of them to participate in both spheres, to teach and also to conduct or manage research. Despite that interdependence, the cost drivers and the planning horizon are quite different. While tuition is an activity that can be organised around annual cycles, research projects usually have longer time-frames. This argues for continuing the separation of funding streams for research and teaching.

Funding that reflects costs …

Any formula for tuition funding needs to reflect costs. That means it needs to take account of the number of people being taught, and the inherent costs of teaching in the field of study. Costs of teaching vary significantly by field; if funding rates are out of kilter with those differences, there are risks to the quality of delivery. Differences of cost by field of study in NZ tertiary education were researched in 2011/12 and many of the imbalances in funding rates corrected[16].

The review needs to satisfy itself that the differentials are still appropriate.

Two factors the review might consider

The review ought consider the new features included in the design of the new unified funding framework for vocational education. That would mean asking if the new HE funding formula might include:

- the characteristics of students – Some students are easier to teach than others. The great majority of undergraduate students in higher education have a university entrance qualification so there is greater homogeneity of preparation for study among entrants to degree study than in vocational education. But analysis of data on student performance identifies factors that predict attrition[17]; understanding what factors increase the risk of attrition can lead to interventions to reduce that attrition.

- mode of delivery – One matter that dogs much higher education in NZ is that – with a few obvious exceptions (like training for the health professions) – there is little integration of education and work. Whereas those studying medicine and nursing have internships built into the structure of their degrees, that is not the case in much non-vocational higher education in this country. Institutions in some other countries (Canada especially[18]) often include work-integrated learning, even in non-vocational programmes. There are real benefits or students in non-vocational programmes from participation in work-integrated-learning. Yet, the funding rates set in 1991 reflected modes of delivery that existed then; if there was no practicum or internship in 1989/90, the rates set then didn’t allow for it, meaning that the current rates still don’t provide for it – this may explain the reluctance of institutions to take up that option now.

The review needs to ask: To what extent should the funding formula allow for those factors? And would including such factors in a funding formula over-complicate it? Are these issues for institutions and government to decide together?

Questions about scale

In her Conversation piece, Nicola Gaston noted that one real winner from the additional injection of funding was the University of Auckland, the one university whose recent and current financial performance shows strength. Yet there are serious economies of scale in tertiary education – there are very high fixed costs but, in most cases, relatively low marginal costs. Yet the current funding formula takes no account of institutional scale. In 1994, an institutional base grant was established designed to mitigate the disadvantage faced by small institutions but that was wiped in the later 1990s.

The question of whether there should be mitigation of the problems of smaller providers needs to be on the agenda of a comprehensive review.

Indexation

TEAC proposed the indexation of funding rates and for a short period, rates were adjusted with inflation. And recently, in an article in Newsroom, Jonathan Boston (who was a TEAC commissioner) argues that indexation is essential.

Governments are often reluctant to index expenditure on the services it provides because indexation represents a commitment on future budgets; therefore, indexation is usually confined to funding streams like welfare benefits where it makes particular sense. Advice to government from officials is likely to suggest that the need for any increase should be analysed and assessed on its merits annually, rather than awarded because of a shift in the price level.

However, we have all seen the risks of that approach in the last few years … in the recent past, funding rates have been fixed in the face of rising costs. The government has been happy to avoid the issue while inflation was relatively low and while the revenue from international students masked the underlying problem. With international student revenue likely to take years to rebuild, that question cannot be avoided in this review.

Time horizon questions

Inevitably, there is a question about the time horizon for funding. Currently, tuition funding is calculated, allocated and delivered annually while most research funding is calculated and allocated over longer time frames – CoREs funding is for five years, while the research quality funding in the PBRF (55% of the PBRF allocation) is fixed for six years. That difference reflects the fact that tuition costs rise and fall annually with enrolments, while research projects are mostly multiyear.

Over the years, there have been calls to extend the horizon for tuition funding, supposedly to facilitate better planning. Some people often hark back wistfully to the years before the Learning for Life reforms when the old university funding system was quinquennial.

However, those of us who worked with the quinquennial system know that it was only ever suitable for extended periods of stability; the 1980s, the last decade of the quinquennial system was anything but stable. There is not the space here to describe just how corrosive quinquennial allocations were, both for government and for institutions and their culture. Put simply, it was a terrible system, inflexible, unresponsive – that’s why it was abandoned.

The question has to be asked. But the answer is simple.

The PBRF

The ministers’ announcement said that the funding system will be reviewed “including the PBRF”. The PBRF is part of the funding system, so a review of the funding system will always have to include the PBRF. That is a matter of logic.

So, why did it receive so much emphasis?

The PBRF was agreed to by the government in 2002. The decision to implement the PBRF included agreement to a set of three evaluative reviews – an implementation review, a review after the second round and then a full evaluation.

In 2004, WEB Research was commissioned to do the evaluation of the implementation and conduct of the first (2003) round. Then, after the second (2006) round, a leading British expert Jonathan Adams was commissioned to conduct the “strategic review[19]” of the system, looking at “near-term benefits to the country; differentiated effects on participants; and potential improvements”. Then we had the evaluative review, led by officials after the 2012 round – leading to further modification of the processes and policy parameters. And in 2020, Linda Tuhiwai Smith led yet another review, resulting in a set of government decisions on how funding is weighted. That’s four PBRF reviews in 19 years! On average, one review every four years and nine months. Each review conducted in consultation with sector informants. Each review leading to changes but confirming the overall underlying architecture. And this is of a fund that works on a six-year cycle. This new review, over 2024/25 will mean that there will have been five reviews of the PBRF before the fifth (2026) round. The scheme will have been reviewed more often than it will have been used!

What were they thinking?

References

Adams J (2008) Strategic review of the Performance-Based Research FundEvidence Ltd

Aziz O, Gibbons M, Ball C and Gorman E (2012) The effect on household income of government taxation and expenditure in 1988, 1998, 2007 and 2010 Policy Quarterly Vol 8 Issue 1

Boston (2002) Evaluating the Tertiary Education Advisory Commission: an insider’s perspective NZ Annual Review of Education, 11, 59-84.

Connew S, Dickson M and Smart W (2015) A comparison of delivery costs and tertiary education funding by field of study: results and methodology Ministry of Education

Crawford R (2016) History of tertiary education reforms in New Zealand Research Note 2016/1, New Zealand Productivity Commission

Curaj A, Matei L, Pricopie R, Salmi J and Scott P (Editors) (2015) The European Higher Education Area: between critical reflection and future policies Springer Open

Deloitte Access Economics (2016) Cost of delivery of higher education Australian Department of Education and Training

Department for Education (2019) Measuring the cost of provision using transparent approach to costing data United Kingdom Department for Education

Earle D (2018) Going on to, and achieving in, higher-level tertiary educationMinistry of Education

Finnie R and Miyairi M (2017) The earnings outcomes of post-secondary co-op graduates Education Policy Research Initiative, University of Ottawa

Frølic N, Schmidt E and Rosa M (2010) Funding systems for higher education and their impacts on institutional strategies and academia: a comparative perspective International Journal of Educational Management Vol. 24 No. 1

Jongbloed B (2010) Funding higher education: a view across Europe European Centre for Strategic Management of Universities

Ministry of Education (2020) Student loan scheme annual report 2019/20 Ministry of Education

Ministry of Education (2017) Student loan scheme annual report 2016/17 Ministry of Education

Nikula P and Morris Matthews K (2018) Zero-fee policy: Making tertiary education and training accessible and affordable for all? NZ Annual Review of Education, 23, 5-19

Norton A (2022a) Inflation and student places under Job-Ready Graduates Higher Education Commentary from Carlton

Norton A (2022b) Submission on priority student funding policy issues for the Universities AccordAustralian Department of Education and Training.

OECD (2022) Expanding and steering capacity in Finnish higher educationOECD Publishing

OECD (2020a) Education at a glance: OECD indicators OECD Publishing

OECD (2020b) Resourcing higher education: challenges, choices and consequences, OECD Publishing

Pruvot E, Claeys-Kulik A and Estermann T (2015), Designing strategies for efficient funding of universities in Europe, European University Association

Roberts P and Peters M (2018) A critique of the Tertiary Education White Paper NZ Annual Review of Education, 8, 5-26

Salerno C (2006) Funding higher education in: File J and Luijten-Lub A (eds) (2006) Reflecting on higher education policy across Europe: a CHEPS resource book Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies, University of Twente

Smart W (2009) Counting the cost: an analysis of domestic tuition fees Ministry of Education

Smyth R (2023a) A tertiary education commission: NZ has one that works Campus Morning Mail

Smyth R (2023b) An expert agency to oversee HE: how it could work Campus Morning Mail

Smyth R (2019) Governments need to think carefully about eliminating tuition fees Times Higher Education

Smyth R (2012) 20 years in the life of a small tertiary education systemOECD

Articles consulted

New Zealand universities’ plans for job cuts

AUT planned job cuts1 News 5 9 22

AUT ordered to restart redundancy processStuff 20 1 23

Massey University planned job cutsRNZ 10 11 22

Massey University planned job cuts Stuff 18 4 23

Massey staff angry as cuts pile up with no consultationTEU 12 7 23

University of Otago planned staff cutsRNZ 31 5 23

Victoria University of Wellington | Te Herenga Waka planned job cuts RNZ 24 5 23

Victoria University of Wellington | Te Herenga Waka planned job cutsNZ Herald 24 5 23

The risks of downsizing our universities– Nicola Gaston, The Spinoff 31 5 23

Additional funding for 2024 and 2025

Government provides significant extra support to universities and other degree providers Ministerial announcement 27 6 23

$128 million boost for struggling tertiary sector welcomed Stuff 27 6 23

Additional funding for tertiary education organisations TEC 27 6 23

New Zealand university funding lifeline ‘welcome but not enough’Times Higher Education 28 6 23

Bailout, Band-Aid or back to basics? 3 questions NZ’s university funding review must ask Nicola Gaston, The Conversation 28 6 23

Major job losses for universities despite govt rescue packageRNZ 27 6 23

Permanent solutions needed after welcome funding correctionTEU 27 6 23

The crisis in tertiary education caused by inadequate funding Jonathan Boston, Newsroom 17 7 23

Appendix 1: The history of reviews of the funding system

The origins of the funding system

A third of a century ago, Gary Hawke, professor of economic history at Victoria University of Wellington, was commissioned by the government to do a comprehensive review of the post-secondary education system. The government’s policy decisions on the Hawke report, called Learning for Life, adopted much of the system architecture proposed by Hawke – and in particular, applying the equivalent full-time student (EFTS) measure to all provider-based tertiary education and using the EFTS as the driver of nearly all funding – for tuition and research[20].

Much of the Learning for Life architecture remains to this day …. Autonomy of public TEIs, TEIs to be responsible for their own capital, systematic formal quality assurance, easing of barriers to the transition of students between sub-sectors …. And bulk funding driven by the number of EFTS.

Settings have been modified, frequently, annually, almost continuously, but many of the principles proposed by Hawke and adopted by the government have endured to the present.

Since then, there have been two comprehensive reviews …

The Todd Report – the Ministerial Consultative Group (MCG)

It’s 29 years since the first major, principles-based, independent review of the Learning for Life funding system. The MCG, led by Jeff Todd, delivered its report in May 1994[21]. Much of the MCG’s focus was on the question: How should the costs of tertiary education be split between government and students? The MCG couldn’t agree on that question and gave the government two options:

- reduce the government’s share to 25% of the full-cost, or

- reduce the government’s share to 50% and use the extra savings to target much greater support to groups who were under-served by the system.

The government picked the first option and the resulting series of progressive funding rate reductions saw students pick up a greater share of the cost, with the loan scheme to maintain affordability and access[22].

The Tertiary Education Advisory Commission (TEAC)

And it’s 21 years since TEAC presented its final report on the second major review of the system. TEAC’s brief was wider than funding but much of their work centred on funding. Their work led the government to make a number of structural changes in the funding system, most notably:

- a stronger ‘steering’ of the system by setting a strategy for the system and creating a government agency to allocate funding in line with the strategy – leading to the creation of the TEC and, after a few false starts, the evolution of the investment plan process

- the unbundling of research funding from tuition funding – leading to the creation of the PBRF and the Centres of Research Excellence

- indexation of funding levels – introduced late in the term of the Clark government, before being abandoned in 2009 when the Key government came in looking for savings in the context of the GFC

- a review of the costs of delivery, leading to an adjustment of the relativities in tuition funding between different fields of study (which took until 2012 to complete[23]).

The government’s decisions on the TEAC’s four reports have underpinned much of the system architecture since – not in every detail, but in principle[24].

…and dozens of tweaks and adjustments …

During the 1990s, the funding system was adjusted pretty much each year – not just the funding levels, but also minor changes to the structure of the system, although without changing the fundamental architecture of the system. Some of the more important were:

- In 1994, the government introduced an institutional base grant, intended to ease the situation of smaller institutions that couldn’t achieve economies of scale. This was abandoned in the late 1990s.

- In 1999, the government moved to “demand-driven” funding, so that every enrolled domestic student would generate funding. It also moved to fund students taking courses at level 3 or above at PTEs on the same basis as those in TEIs.

- In 2001 and 2002, institutions were given additional funding in exchange for freezing fees.

- In 2004, the fees freeze was lifted and replaced by controls on fee increases.

- In 2007, the government moved to phase out demand-driven funding, with effect from 2009. Instead, funding would be demand led meaning that funding would take account of forecast demand

- In 2010, the government introduced a set of standard performance indicators that were later used as the basis of performance-linked funding (PLF); 5% of a TEO’s funding could be reclaimed if the TEO was rated poorly on those measures. PLF was abandoned in 2018.

- In 2018, the government made each New Zealander’s first year of tertiary education fees free by paying the TEO an amount equal to the fees foregone.

Endnotes

[1] The Ministry forecasts only at system level, not at an institutional level. This means that, if some institutions do well in 2023, others are likely to do worse. The minister was quoted by Stuff as stating that institutions were forecasting growth but that the opposite occurred. Possibly. And if so, one or two institutions may have been surprised by the result. But that is a red herring. The allocations are influenced by the official forecasts (which were accurate). So, if the institutions were surprised, the minister wasn’t. She knew in advance that domestic intakes were falling.

[2] This uses CPI for Q1 in each year using the RBNZ calculator. The actual readings were 6.9% for the 2021 to 22 CPI, and 6.7% for 2022 to 23.

[3] The correlation coefficient is 0.72. The adjusted EFTS to FTE ratio explains just over 50% of the variation in surplus as a percentage of revenue.

[4] See Appendix 1 for a fuller account of the history of the development of the funding system, the Hawke report, the MCG, TEAC and the annual changes to the funding system.

[5] Refer especially to Smyth (2023a and 2023b)

[6] Refer to Roberts and Peters (2018)

[7] Refer to Boston (2002)

[8] The Productivity Commission, the Health and Disability Commission and the Electoral Commission are examples of independent crown entities (ICEs). For the rights and roles of each type of Crown entity, refer to the Crown Entities Act. Jonathan’s disappointment is misplaced – most ICEs are set up to hold government to account on policy issues, not to create or advise on policy.

[9] The Beehive release quotes Minister Tinetti as saying “It should be noted that while recent focus has been on Victoria and Otago Universities, other institutions have previously managed declines in student numbers. We did not want to disadvantage those institutions which in some cases had already made difficult decisions”. The implication is that she sees the problem as having been soluble, but that some institutions didn’t read the tealeaves right.

[10] Refer in particular to: Curaj et al (2015), Frølic at al (2010), Pruvot et al (2015) and Salerno (2006)

[11] Refer to information about the Australian Universities Accord and to Wonkhe discussion papers on UK HE resourcing issues.

[12] See Norton (2022a and 2022b).

[13] In relation to student allowances, we need to recognise that the gradual loss of targeting in the student allowances scheme since 2004 has rendered that system all but useless; it supports too many students and for those who really do need this support, it provides far too little support and an overly narrow range of supports. That’s a matter for another article.

[14] An interesting example is Finland – refer to this OECD report.

[15] There is a vast literature on this topic. For the purposes of this discussion, see Smyth (2019), Nikula and Morris Matthews (2018), Aziz et al (2012), OECD (2020a and 2020b)

[16] See Connew et al (2012). Similar exercises have been done in Australia and the UK – see Deloitte Access Economics (2016) and Department for Education (2019).

[17] See Earle (2018)

[18] See this description and the analysis of the outcomes of those who take work-integrated learning in Finnie and Myairi (2017)

[19] See Adams (2008)

[20] The main references used in this section are Smyth (2012 and 2023), Crawford (2016) and Boston (2002).

[21] Ministry of Education (1994) Funding growth in tertiary education and training: The report of the Ministerial Consultative Group, Ministerial Consultative Group, Ministry of Education.

[22] In fact, the government beat the 25% target. In 2000, the student share was around 33%. Fee controls meant that fell to 29% in 2016 before falling further (to around 23%) after the introduction of fees-free first year tertiary education in 2019. See the annual reports on the student loan scheme for the data.

[23] See Connew et al (2015)

[24] Refer especially to Smyth (2023a and 2023b)